Vectors#

Before delving into the core presentation of vectors, it is crucial to establish a foundational understanding of coordinate systems.

Coordinate systems#

A coordinate system, often referred to as a reference frame (or simply as a frame or system for brevity), is a fundamental concept in mathematics and geometry. It provides a way to uniquely determine a position in space by using one or more numbers called coordinates.

To define a coordinate system, three key components are needed: an origin, a unit of measurement, and a positive direction. The origin is a reference point from which all positions are measured. The unit of measurement determines the scale or size of each coordinate value. The positive direction indicates how the coordinates increase from the origin.

By using a coordinate system, we can bridge the gap between geometry and numerical problems. Geometrical problems involving positions, distances, angles, and shapes can be translated into numerical problems by assigning coordinates to the geometric elements. Similarly, numerical problems can be visualized and understood geometrically by mapping the numbers that represent points and other geometric entities onto a coordinate system.

1D Coordinate system#

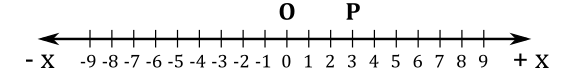

A 1D coordinate system is a reference frame that operates along a single dimension, typically represented by a straight line (but it can also be a curve). In a 1D coordinate system, an origin point is typically defined as a reference point for the line. This origin point serves as the starting point from which positions are measured. Additionally, it is necessary to establish a unit of measurement that determines the scale or increment used to quantify distances or positions along the line, and a positive direction indicating the way in which values increase from the origin. In this type of coordinate system, a position \(\mathbf{P}\) on a line (or curve) can be determined with a single number (coordinate) \(x\).

For instance, in the line illustrated above, \(x=3\) specifies that the position \(\mathbf{P}\) is \(3\) units away from the origin \(\mathbf{O}\) in the positive direction along the line. This approach assigns a unique coordinate to each point\position on the line, and every real number representing the coordinate of a distinct point on the line. Therefore, the coordinate of a point \(\mathbf{P}\) is defined as the signed distance between the origin \(\mathbf{O}\) and the point.

Cartesian coordinate system#

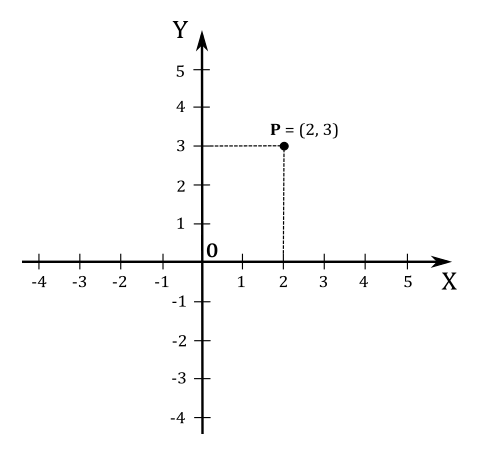

In two dimensiones (i.e., in a plane), two perpendicular lines (also called axes) define a system. We can express the coordinates \((x, y)\) of a point \(\mathbf{P}\) as the signed distances between the origin \(\mathbf{O}\) and the projection of \(\mathbf{P}\) onto the axes.

For example, point \(\mathbf{P}\) in the illustration above has coordinates \((2, 3)\) because its projection is two units away from \(\mathbf{O}\) along the x-axis and three units away from \(\mathbf{O}\) along the y-axis.

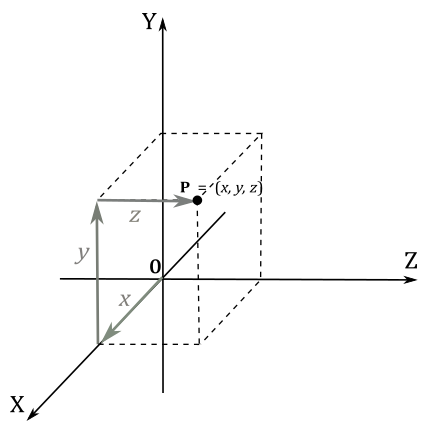

In three dimensions, three mutually perpendicular axes define a system. The coordinates \((x, y, z)\) of a point represent the signed distances between the origin \(\mathbf{O}\) and the projections of the point onto the axes.

Note

To project a point \(\mathbf{P}\) onto the x-axis, imagine first projecting the point perpendicularly onto the xz-plane, bringing you back to the 2D case. Then, project the result onto the x-axis. A similar approach can be used to compute the projection onto the other two axes.

You can also view the coordinates \((x, y, z)\) as a series of steps from the origin \(\mathbf{O}\) to point \(\mathbf{P}\):

Move \(x\) units along the x-axis.

From that position, move \(y\) units parallel to the y-axis.

Finally, move \(z\) units parallel to the z-axis.

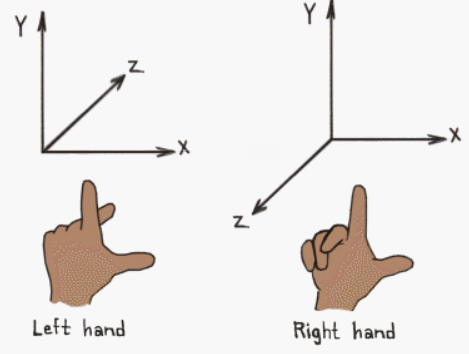

Depending on the direction and order of the axes, a three-dimensional system can be right-handed or left-handed.

Typically, the y-axis points up, the x-axis points right, and the z-axis points forward (note that forward aims at different directions depending on whether a right-handed or left-handed coordinate system is being used). However, this isn’t a strict rule. Sometimes, you can have the z-axis points up, and in that case the y-axis points forward. You can always switch from a y-up to a z-up configuration with a simple transformation, but there’s no point in providing further details here as we will use z-up or y-up configurations consistently during the rendering process (further details will be provided as needed).

It seems that DirectX programmers commonly use left-handed systems, so we’ll adopt this convention in this tutorial series. However, remember that right-handed systems are also valid for use in DirectX.

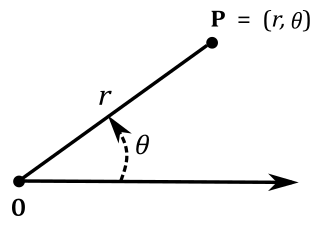

Polar coordinate system#

In a two-dimensional plane, we can define a coordinate system called the polar coordinate system. This system relies on two key elements:

Origin (or pole): A fixed reference point.

Polar axis: A ray extending from the origin.

A point \(\mathbf{P}\) is identified by its polar coordinates, \((r,\theta)\), where:

\(r\): Represents the distance from the origin to point P. This distance is also called the radius.

\(θ\): Represents the angle between the polar axis and the line segment connecting the origin and point P. This angle is usually measured in degrees or radians (\(2\pi\) radians =\(360°\)).

Note

A single point can have multiple polar coordinate representations due to the periodicity of angles. For example, \((r,\theta)\) and \((r,\theta + 2\pi)\) represent the same point. Be aware of this when working with polar, cylindrical or spherical coordinates.

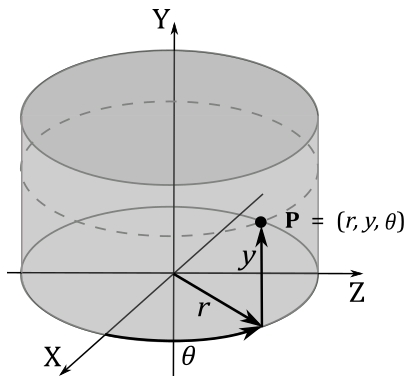

Cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems#

Extending polar coordinates, we can add an extra y-coordinate to specify the height from the plane containing origin and polar axis. This way, we can locate all points on a cylinder in three dimensions, hence the name “cylindrical coordinates” represented by the triple \((r, y, \theta)\).

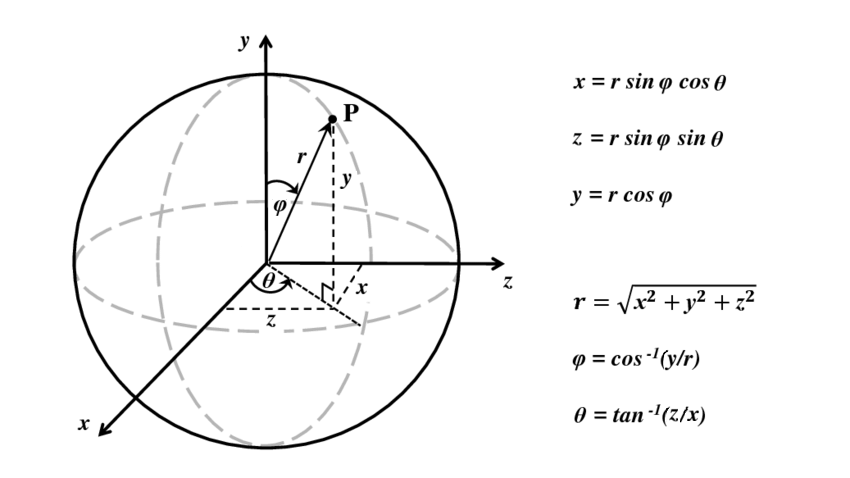

Build upon cylindrical coordinates, we can obtain spherical coordinates by converting the height \(y\) into and angle \(\varphi\) within the range \([0, 180°]\). This gives us the triple \((r, \varphi, \theta)\), which identifies all points on a sphere. The following illustration shows the conversion between spherical and Cartesian coordinates. Observe that the angle \(\varphi\) is measured from the upward direction.

Homogeneous coordinate system#

In homogeneous coordinates, a point in a plane can be represented by a triple \((x, y, z)\). By dividing each coordinate by the z-coordinate, we can obtain the corresponding Cartesian coordinates: \((x/z,\ y/z,\ z/z)\). Obviously, this approach introduces an additional coordinate, even though typically only two coordinates are used to specify a point in a two-dimensional space. Nevertheless, homogeneous coordinates enable us to express various transformations, such as scaling, rotation, and translation, in a simple and consistent way using matrices.

Important

In general, a homogeneous coordinate system is a frame where only the ratios of the coordinates are significant, rather than their actual values.

Note

After performing the division to obtain the Cartesian coordinates, the last coordinate will always be 1. This concept extends to three-dimensional spaces as well. Therefore, if we have the 3D Cartesian coordinates \((x, y, z)\), we can also express them as \((x, y, z, 1)\).

Vectors#

Vectors are mathematical objects that represent quantities with both magnitude and direction. They are used in many fields, including physics and computer graphics. For example, vectors can be used to specify the position and displacement of objects, as well as their speed. They can also describe the direction and intensity of forces acting on objects or light rays emitted by a light source, as well as surface normals. For a more extensive and detailed presentation on vectors, you may find valuable information in [FH21] and [SE02].

Definition#

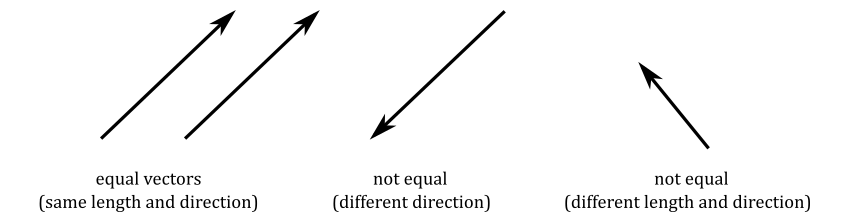

Geometrically, a vector can be visualized as an arrow. The length of the arrow represents the magnitude or size of the vector, while the direction in which the arrow points indicates the direction of the vector.

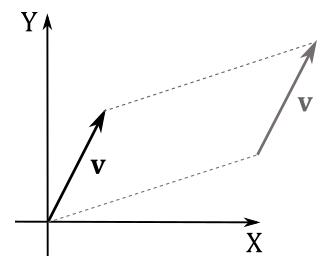

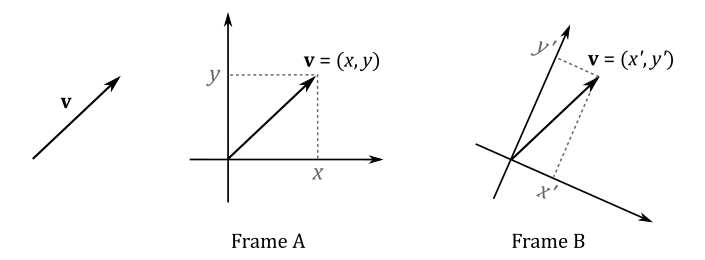

When working with vectors for numerical computation on a computer, the geometric definition provided above is not as important, although. Fortunately, we can express vectors numerically using tuples, which are finite sequences of numbers. To establish this numerical representation, we need to bind vectors to the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system. In other words, we translate a vector while maintaining its magnitude and direction until its starting point aligns with the origin.

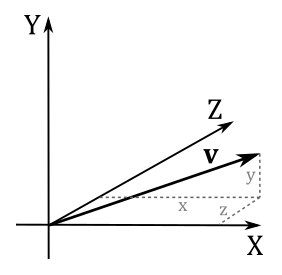

At that point, we can use the coordinates \((x, y)\) of the head of a generic vector \(\mathbf{v}\) in a 2D Cartesian system as the numerical representation of the vector in that system. That is, we can write \(\mathbf{v}=(x, y)\), with \(x\) and \(y\) called components of the vector. Similarly, for a vector \(\mathbf{v}\) in a 3D Cartesian system, the numerical representation would be \((x, y, z)\). Then, we can use \(\mathbf{v}\) to specify a point in a frame (maybe to set the position of an object, or a target location for movement).

When only magnitude and direction of a vector matter, then the point of application is of no importance, and the vector is called free vector. On the other hand, a vector bound to the origin of a system is called bound vector. The numerical representation of a bound vector is only valid in the system where it is bound. If the same free vector is bound to different systems, its numerical representation will change accordingly.

Important

This is an important point to remember: if you define a vector numerically, its coordinates are relative to a specific reference frame. Therefore, we can conclude that two vectors \(\mathbf{u}=(u_x, u_y, u_z)\) and \(\mathbf{v}=(v_x, v_y, v_z)\) are equal only if \(u_x=v_x\), \(u_y=v_y\) and \(u_z=v_z\). In other words, they have equal coordinates if bound to the origin of the same frame.

Basic operations#

Vectors support various interesting operations, including addition, subtraction, and three types of multiplication.

Addition and Subtraction#

Numerically, the sum of two vectors \(\mathbf{u}=(u_x, u_y, u_z)\) and \(\mathbf{v}=(v_x, v_y, v_z)\) is defined as

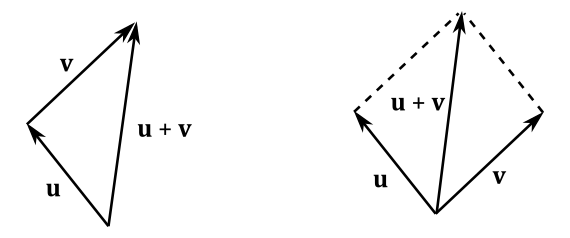

The addition may be represented geometrically by placing the tail of the arrow representing \(\mathbf{v}\) at the head of the arrow representing \(\mathbf{u}\), and then drawing an arrow from the tail of \(\mathbf{u}\) to the head of \(\mathbf{v}\). This arrow represent a new vector as the sum of \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\). Alternatively, we can bind \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) to a shared point and then draw the diagonal of the parallelogram with sides \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\).

The difference between two vectors \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is defined as

Geometrically, the vector subtraction can be defined by bounding \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) to a shared point and drawing an arrow from the head of \(\mathbf{v}\) to the head of \(\mathbf{u}\). Alternatively, it can be treated as a sum \((\mathbf{u}+(-\mathbf{v}))\) by placing the tail of the inverse of \(\mathbf{v}\) at the head of \(\mathbf{u}\). At that point, we can draw an arrow from the tail of \(\mathbf{u}\) to the head of \(-\mathbf{v}\). This arrow represent a new vector as the difference between \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\). The inverse of a vector will be formally defined in the next section.

Scalar multiplication#

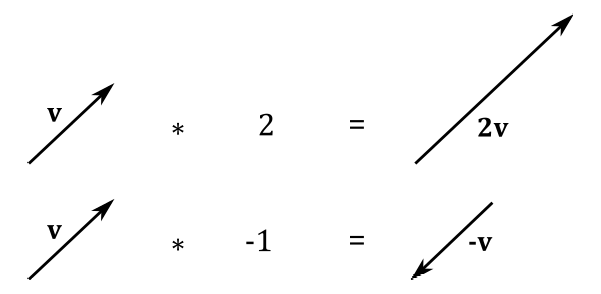

We can multiply a vector \(\mathbf{v}=(x, y, z)\) by a real number \(k\) called scalar. Numerically, this operation is defined as

Geometrically, this is equivalent to scaling a vector, which is why real numbers are often called scalars. If \(k\) is negative, the resulting vector will aim in the opposite direction as well. In particular, if \(k=−1\) we get the inverse \(-\mathbf{v}\) of a vector \(\mathbf{v}\), which aims in the opposite direction without changing its length.

Properties of addition and scalar multiplication#

Here are some of the properties of vector addition and scalar multiplication:

Name |

Property |

|---|---|

Commutative (vector) |

\(\mathbf{u}+\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{v}+\mathbf{u}\) |

Associative (vector) |

\((\mathbf{u}+\mathbf{v})+\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{u}+(\mathbf{v}+\mathbf{w})\) |

Additive Identity |

\(\mathbf{v}+\mathbf{0}=\mathbf{v}\) (where \(\mathbf{0}\) is the zero (or null) vector, whose components are all zero) |

Distributive (vector) |

\(k(\mathbf{u}+\mathbf{v})=k\mathbf{u}+k\mathbf{v}\) |

Distributive (scalar) |

\((k+t)\mathbf{v}=k\mathbf{v}+t\mathbf{v}\) |

Associative (scalar) |

\(k(t\mathbf{v})=(kt)\mathbf{v}\) |

Multiplicative Identity |

\(1\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{v}\) (where \(k=1\) is a scalar) |

Length of a vector#

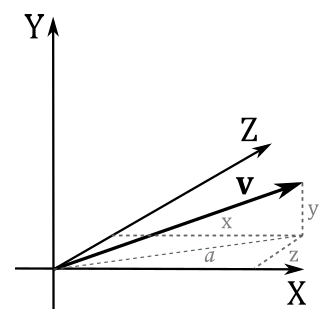

Now, we can define the length of a vector \(|v|\) (or \(\|v\|\)) as a scalar value that represents the magnitude of the vector. Consider the following illustration.

We have that \(a\) is the length of the projection of the vector \(\mathbf{v}\) onto the xz-plane. From the Pythagorean theorem, \(a=\sqrt{x^2+z^2}\). Then, applying the same theorem once again, we have that

Sometimes, only the direction of a vector is relevant. In such cases, we can normalize the vector to ensure its length becomes 1. Usually, the symbol \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\) is used to indicate a unit vector (a vector with length 1). To normalize a vector \(\mathbf{v}=(x, y, z)\), we can multiply it by the reciprocal of its magnitude.

We can verify that \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}\) is a unit vector by computing its length.

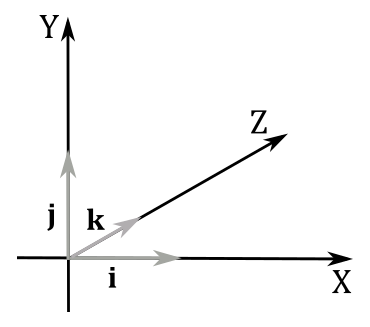

Three significant unit vectors are: \(\mathbf{i}=(1,0,0)\), \(\mathbf{j}=(0,1,0)\) and \(\mathbf{k}=(0,0,1)\). These vectors have unit lengths and align with the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively, in a 3D Cartesian coordinate system. They are commonly referred to as the standard basis vectors of a coordinate system.

Dot product#

The dot product is a form of vector multiplication that results in a scalar value ─ it is also known as the scalar product for this reason. The dot product of two vector \(\mathbf{u}=(u_x, u_y, u_z)\) and \(\mathbf{v}=(v_x, v_y, v_z)\) is defined as

In essence, the dot product of two vectors is obtained by summing the products of the corresponding components.

Properties of dot multiplication#

Below are some of the properties of the dot product:

Name |

Property |

|---|---|

Commutative |

\(\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{u}\) |

Distributive |

\((\mathbf{u}+\mathbf{v})\cdot\mathbf{w}=\mathbf{w}\cdot(\mathbf{u}+\mathbf{v})=(\mathbf{w}\cdot\mathbf{u})+(\mathbf{w}\cdot\mathbf{v})\) |

Square of a vector length |

\(\|\mathbf{v}\| ^2=v_x^2+v_y^2+v_z^2=\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{v}\) |

The associative property doesn’t apply because \(\mathbf{w}\cdot(\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v})\) is not defined. Indeed, the dot product is defined as an operation between two vectors, but \((\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v})\) yields a scalar value.

Moreover, from the law of cosines \(c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab\cos{\theta}\) (a proof is provided at the end of the section), we can show that

Indeed, if we set \(a=|\mathbf{u}|\), \(b=|\mathbf{v}|\) and \(c=|\mathbf{u}-\mathbf{v}|\) we have that

From equation \(\eqref{eq:Avectors1}\), we can derive other properties. For example,

If \((\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) = 0\) then the angle \(\theta\) between \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is \(90°\) (that is, they are orthogonal: \(\mathbf{u}\ \bot\ \mathbf{v}\))

If \((\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) > 0\) then the angle \(\theta\) between \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is less than \(90°\)

If \((\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{v}) < 0\) then the angle \(\theta\) between \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is greater than \(90°\)

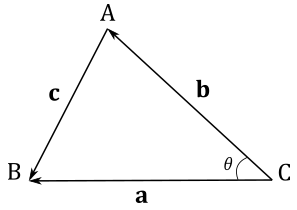

To conclude this section, we will prove the law of cosines: \(c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab\cos{\theta}\).

Proof

Let \(\mathbf{a}\) be the vector from \(C\) to \(B\), \(\mathbf{b}\) the vector from \(C\) to \(A\), and \(\mathbf{c}\) the vector from \(A\) to \(B\).

We have that

Squaring both sides and simplifying

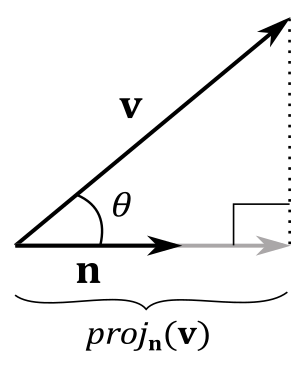

Orthogonal projection#

The orthogonal projection of a vector \(\mathbf{v}\) onto another vector \(\mathbf{n}\) is defined as the vector \(\text{proj}_\mathbf{n}(\mathbf{v})\). Consider the following illustration.

From trigonometry, we know that, in a right triangle, the cosine of an angle equals the ratio between the length of the adjacent side and the length of the hypotenuse. Therefore, we can calculate the length of the adjacent side by multiplying the length of the hypotenuse by the cosine of the angle between the adjacent side and the hypotenuse. Considering the image above, we have that \(|\text{adj}|=|\text{proj}_\mathbf{n}(\mathbf{v})|\) and \(|\text{hyp}|=|\mathbf{v}|\). So, if \(\mathbf{n}\) is a unit vector, we can write

with \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\) signed length of the projection, and \(\mathbf{n}\) that indicates its direction. This means that \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\) can invert the direction of projection if \(\theta > 90°\). Anyway, this gives us a geometrical interpretation of the dot product, at least if \(\mathbf{n}\) is a unit vector. If that’s not the case, we can always normalize \(\mathbf{n}\) to make it unit length. Then, we can replace \(\mathbf{n}\) with its normalized version \(\mathbf{n}/|\mathbf{n}|\), giving us the more general formula

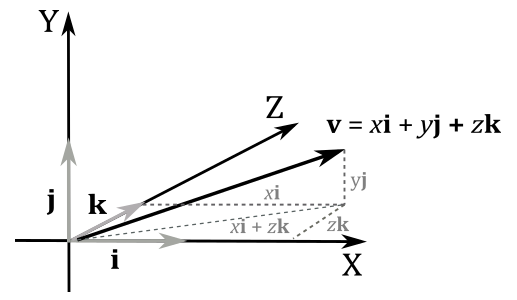

Thanks to the concept of orthogonal projection, we can express any bound vector \(\mathbf{v}\) as the sum of its projections onto the standard basis vectors as follows:

Indeed, we have

Also, note that \((x\mathbf{i}+z\mathbf{k})\) is the projection of \(\mathbf{v}\) onto the xz-plane, so that we can sum this projection with \(y\mathbf{j}\) to get \(\mathbf{v}\).

Note

You can also see it as a sum of scaled vectors: we scale \(\mathbf{i}\), \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{k}\) with the corresponding components of \(\mathbf{v}\). Indeed, the diagonal of the parallelogram defined by \(x\mathbf{i}\) and \(z\mathbf{k}\) is \((x\mathbf{i}+z\mathbf{k})\), while \(\mathbf{v}\) is the diagonal of the parallelogram defined by \((x\mathbf{i}+z\mathbf{k})\) and \(y\mathbf{j}\), that is \(\ x\mathbf{i}+z\mathbf{k}+y\mathbf{j}\).

As mentioned earlier, you can express every vector as a sequence of three steps\translations: starting from the origin of the frame, we move \(x\) units along the x-axis. Then, from that position, we move \(y\) units in the y-axis direction, and finally, you move \(z\) units in the z-axis direction. This is why we refer to \(\mathbf{i}\), \(\mathbf{j}\), and \(\mathbf{k}\) as basis vectors: any bound vector in a frame can be expressed as a combination of these three unit vectors, with the components of the vector acting as coefficients.

The components of a bound vector represent the coordinates of its arrowhead within the frame. This allows us to uniquely identify all points within a frame using vector notation. However, we still need a way to distinguish between vectors and points, as they are not interchangeable. For vectors, only their direction and magnitude matter, making the point of application irrelevant. On the other hand, points uniquely represent a location and only make sense when bound to the origin of a frame. Subtracting points yields a vector that specifies the movement from one point to another, while adding a point and a vector gives a vector that specifies how to move a point to a different location. However, unlike vectors, adding two points does not have a meaningful interpretation ─ geometrically it’s the diagonal of a parallelogram, but this interpretation is not particularly useful or relevant when working with points.

In summary, consider vectors as free vectors and points as bound vectors. When working with a generic vector \(\mathbf{v}=(x, y, z)\), it is crucial to determine whether it represents a point or a vector to use it appropriately. The distinction between points and vectors will be further explored in a later tutorial.

Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization#

A computer cannot exactly represent all elements in the infinite set of real numbers because it uses a finite number of bits to store values in memory. This means that we must to settle for good approximations. The downside is that, if you need to perform many calculations with approximate values, the outcome could differ significantly from the exact result. For example, a set of vectors \(\{\mathbf{v_0},\dots,\mathbf{v_{n-1}}\}\) is called orthonormal if they are all unit vectors and orthogonal to each other. However, due to numerical precision issues, we might start off with an orthonormal set that gradually becomes un-orthonormal after some transformations. Fortunately, there are methods available to orthogonalize a set of vectors to restore its orthonormality. While our primary focus will be on the 3D case, it is often helpful to start by examining the simpler 2D case.

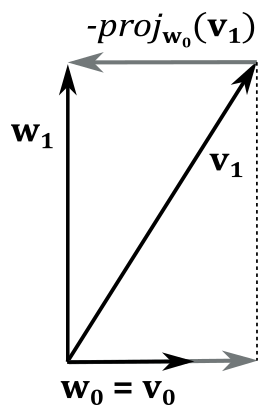

Suppose we have an initial set of vectors \(\{\mathbf{v_0},\mathbf{v_1}\}\) that is not orthonormal, and we want to orthogonalize it to obtain an orthonormal set \(\{\mathbf{w_0},\mathbf{w_1}\}\). To begin the orthogonalization process, we can set \(\mathbf{w_0}=\mathbf{v_0}\), as we can always assume one of the vectors in the set is already acceptable. Next, we aim to make \(\mathbf{v_1}\) orthogonal to \(\mathbf{w_0}\). This can be achieved by subtracting from \(\mathbf{v_1}\) its projection onto \(\mathbf{w_0}\). By doing so, we obtain a new vector \(\mathbf{w_1}\) that is orthogonal to \(\mathbf{w_0}\). Indeed, in the following illustration, you can verify that

So, we have that

where \(\ \text{proj}_{\mathbf{w_0}}(\mathbf{v_1})=\displaystyle\frac{\mathbf{v_1}\cdot\mathbf{w_0}}{|\mathbf{w_0}|^2}\mathbf{w_0}\)

To prove that \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and \(\mathbf{w_1}\) are orthogonal to each other, we can first observe that a projection is orthogonal if the direction of projection forms a right angle \((90°)\) with the vector we project onto (see the dashed line in the illustration above). Also, we know that the sum of two vectors is the diagonal of the parallelogram with sides the two vectors. In this case we obtain a rectangle since we just established that an angle of the parallelogram with diagonal \(v_1\) is \(90°\). So, we verified that \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and \(\mathbf{w_1}\) are orthogonal: \(\mathbf{w_0}\ \bot\ \mathbf{w_1}\).

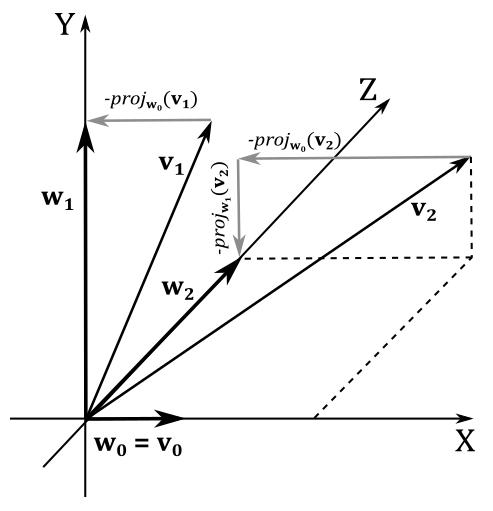

In the 3D case, we introduce a third vector \(\mathbf{v_2}\) that we need to modify in order to make it orthogonal to both \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and \(\mathbf{w_1}\). As before, we start by setting \(\mathbf{w_0}=\mathbf{v_0}\), and we can still use the method of subtracting the projection of \(\mathbf{v_1}\) onto \(\mathbf{w_0}\) to compute \(\mathbf{w_1}\). This is possible because we can consider \(\mathbf{v_0}\) and \(\mathbf{v_1}\) as lying in the same plane, thereby reducing the problem to the 2D case. To calculate \(\mathbf{w_2}\), we proceed similarly. We subtract the projection of \(\mathbf{v_2}\) onto \(\mathbf{w_0}\) from \(\mathbf{v_2}\), obtaining an intermediate vector. Then, we can subtract the projection of \(\mathbf{v_2}\) onto \(\mathbf{w_1}\) from this intermediate vector. By doing this, we ensure that the resultant vector \(\mathbf{w_2}\) is orthogonal to both \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and \(\mathbf{w_1}\).

Consider the illustration below. If we subtract \(\text{proj}\_{\mathbf{w_0}}(\mathbf{v_2})\) from \(\mathbf{v_2}\) the resultant vector is orthogonal to \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and lies in the YZ-plane. Then, if we subtract \(\text{proj}\_{\mathbf{w_1}}(\mathbf{v_2})\) from this intermediate vector, we get \(\mathbf{w_2}\), which is orthogonal to both \(\mathbf{w_0}\) and \(\mathbf{w_1}\).

The final step in the process of orthogonalization is to normalize the vectors \(\mathbf{w_0}\), \(\mathbf{w_1}\), and \(\mathbf{w_2}\) to obtain an orthonormal set.

Cross product#

This type of multiplication, also known as the vector product, differs from the dot product by resulting in a vector instead of a scalar. It’s defined as follows:

A way to remember this formula is to notice that the first component of the vector \(\mathbf{w}\) is missing the subscript \(x\), the second component is missing the subscript \(y\), and the third component is missing the subscript \(z\). The trick works by using the subscripts \(\{x,y,z\}\) as a circular sequence. For example, in the first component of \(\mathbf{w}\) we exclude the subscript \(x\), so we start with \(y\) and \(z\) in the minuend, inverting the subscripts in the subtrahend. In the second component we exclude the subscript \(y\), so we start with \(z\) and \(x\) in the minuend, inverting the subscripts in the subtrahend. You can easily conclude that the third component starts with \(x\), followed by \(y\).

Note

We can also use matrices to calculate the cross product. For example, the cross product \(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\) is equal to the determinant of the \(3\times 3\) matrix with \(\mathbf{i}\), \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{k}\) as elements of the first row, and the components of the two vectors \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) as elements of the other two rows.

Also, the cross product can be computed multiplying a row vector by a matrix.

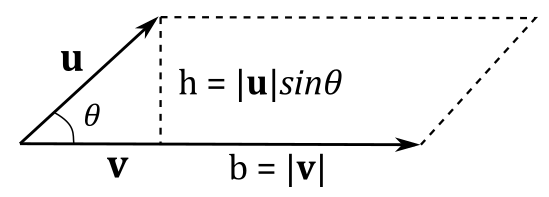

We will cover matrices in the next appendix, where we will show that the determinant of a matrix is related to the concept of hypervolume (that is, length in 1D, area in 2D, and volume in 3D). However, in this section we can use the information provided in the box note above to find something interesting. We know that two vectors always lie in a plane, and that to calculate the area of a parallelogram we multiply its base times the height. Then, we are supposed to find a similar formula for the cross product because, to compute it, we can use the determinant of a matrix, which is related to the concept of hypervolume (area in the 2D case). Indeed, we can also write the cross product as follows:

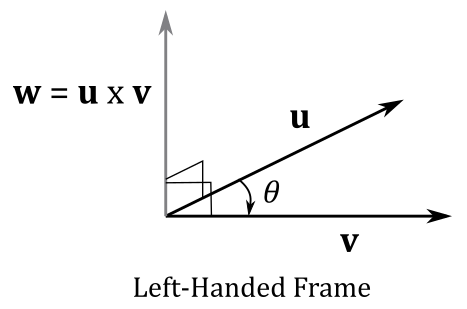

with \(\mathbf{n}\) unit vector indicating the direction of \(\mathbf{w}\), and with \(|\mathbf{u}||\mathbf{v}|\sin{\theta}\) indicating the length of \(\mathbf{w}\). The vector \(\mathbf{n}\) is often called normal, which means it is orthogonal to the surface it refers to (in this case, the plane defined by \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\)). Now, we need to find a connection between the above formula and the area \(A_p\) of the parallelogram with sides \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\). Consider the following illustration.

We know that \(A_p=b\times h\), so we should have something like

since \(|\mathbf{n}|=1\) and the area of a parallelogram is a scalar value, so that we must consider the length of the cross product. As you can see in the illustration above, we have \(|\mathbf{v}|=b\) and \(|\mathbf{u}|\sin{\theta}=h\). So, it’s \(A_p=|\mathbf{w}|=|\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}|\) as expected. We just found a geometric representation of the length of the cross product.

As just stated above, the vector \(\mathbf{n}\) is orthogonal to the plane defined by \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\). So, the resultant vector \(\mathbf{w}\) of the cross product is orthogonal to both \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) as well. Ok, but we have two sides that \(\mathbf{w}\) could aim at. Which side is the right one? In left-handed systems, it’s the one that makes \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\) a left-handed system. While we don’t have a formal definition yet to establish if a set of three vectors composes a left-handed system, you can still identify the correct side.This is the side where \(\mathbf{w}\) “sees” the first operand (in this case \(\mathbf{u}\)) rotate clockwise toward the second operand \((\mathbf{v})\) with an angle of rotation \(θ\) in \([0, \pi]\). Alternatively, you can also use your left hand: align your fingers with the direction of \(\mathbf{u}\), curl them towards \(\mathbf{v}\), and your thumb will point in the direction of \(\mathbf{w}\).; this is called the left-hand-thumb rule.

In right-handed systems, the correct side is the one that makes \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\) a right-handed system.

The commutative property doesn’t apply \((\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\ne\mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{u})\) as if you swap the vectors \(\mathbf{u}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) the direction of \(\mathbf{w}\) changes as well (you can check it with the left-hand-thumb rule). However, you can easily verify that the following equivalence is true.

And we also have that

A way to remember the above equivalences is to consider the unit vectors \(\{\mathbf{i},\mathbf{j},\mathbf{k}\}\) as a circular sequence. If you cross multiply a vector by the next one, you get the third vector with a positive sign. Otherwise, you get a negative sign. Observe that if you cross multiply a vector by itself the result is the zero vector (or null vector, where all components are zero and the direction is undefined) as you can’t build a parallelogram with two equal vectors ─ you get a segment, so the area is zero.

Scalar and vector triple product#

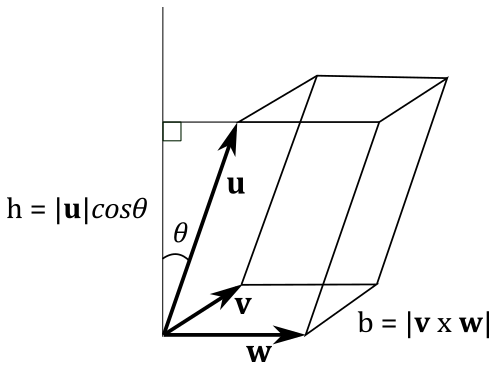

The scalar triple product is nothing really new, as it simply combines the dot product and the cross product. It is defined as:

where \(V\) represents the volume of the parallelepiped formed by the bound vectors \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v}\), and \(\mathbf{w}\). Consider the following illustration.

As you know, the length of the cross product is the area of a parallelogram. Also, the volume of a parallelepiped is \(V=b\times h\). Therefore, in order to compute the volume of the parallelepiped illustrated above, we can to write

with \(|\mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{w}|=b\) and \(|\mathbf{u}|\cos{\theta}=h\).

From equation \(\eqref{eq:Avectors1}\) we can also write it as

which is the scalar triple product. If you expand it you have

which is exactly the determinant of the \(3\times 3\) matrix with \(\mathbf{u}\), \(\mathbf{v}\) and \(\mathbf{w}\) as columns, or rows. The upcoming appendix on matrices will provide further details of this result and illustrate how the scalar triple product can be used to determine if a set of three vectors forms a right-handed system. In brief, if the triple scalar product of three bound vectors defined in a right-handed system is positive, then they form a right-hand system.

We conclude this section pointing out that a vector triple product \(\mathbf{a}\times(\mathbf{b}\times \mathbf{c})\) also exists. However, we will only demonstrate the following identity, called the BAC-CAB identity.

Proof

Below, you can observe that the first component of \(\mathbf{b}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{c})-\mathbf{c}(\mathbf{a}\cdot\mathbf{b})\) (the one highlighted in red) is equivalent to the first component of \(\mathbf{a}\times(\mathbf{b}\times\mathbf{c})\)

The same applies to the other two components.

Vectors in DirectX#

Vectors play a crucial role in computer graphics, making them a fundamental tool to use in DirectX applications as well. They are widely used in both C++ and in HLSL.

HLSL#

In HLSL, vectors of two, three and four floating-point components are represented by the built-in types float2, float3 and float4, respectively. For vectors of signed integers, we use int2, int3 and int4 ─ the unsigned version can be specified by replacing the prefix i with u. Alternatively, we can use the keyword vector to declare vectors by using a template syntax to specify number and type of the components.

The shader model defines 128-bit shader core registers to hold both integer and floating-point vectors to perform SIMD operations (more on this shortly).

The components of a vector can be accessed using the subscript operator [] to provide array indexing. Alternatively, one of the following naming sets can be used:

The position set: \(\ x,y,z,w\)

The color set: \(\ r,g,b,a\)

Specifying one or more vector components is called swizzling. For example:

vector<int, 1> iVector = 1; // int iVector = 1;

vector<float, 4> dVector = { 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 }; // float4 dVector = { 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 };

float4 u = { 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 0.0f };

float f0 = u.x; // f0 = 1.0f

float f1 = u.g; // f1 = 2.0f

float f2 = u[2]; // f2 = 3.0f

u.a = 4.0f; // u = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f)

float4 v = { 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f };

float3 vec1 = v.xyz; // vec1 = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

float2 vec2 = v.rb; // vec2 = (1.0f, 3.0f)

float4 vec3 = v.zzxy; // vec3 = (3.0f, 3.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f)

vec3.wxyz = vec3; // vec3 = (3.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

vec3.yw = vec1.zz; // vec3 = (3.0f, 3.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f)

float4 w = float4(vec1, 5.0); // w = (1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 5.0f)

C++#

Using vectors in C++ is not as straightforward as in HLSL because there are no built-in types available. However, the XMVECTOR type, defined in the DirectXMath.h header file provided by the DirectX math API (DirectXMath), allows us to create variables that map to 128-bit CPU registers.

typedef __m128 XMVECTOR;

In other words, a __m128 variable is backed by a memory region of 128 bits that the compiler can use as a source\destination to load\store data in\from XMM[0-7] registers, which are used in SIMD instructions. SIMD (single instruction multiple data) allows us to perform more operations with a single instruction.

To better understand how SIMD works, it’s useful to consider a practical example.

First, it is worth noting that in DirectX, using vectors with four components is quite common, where each component consists of 4-byte to represent a floating-point or integer value.

Note

You may wonder why DirectX provides four-component vectors if we primarily operate in 3D space (which typically requires only 3 coordinates). As we’ll explore in a subsequent tutorial, introducing an additional coordinate proves useful to differentiate between free and bound vectors. In other words, we’ll operate in a homogeneous coordinate system to enable us to work with both points and vectors using a unified representation. But don’t worry, it is simpler than it may seem.

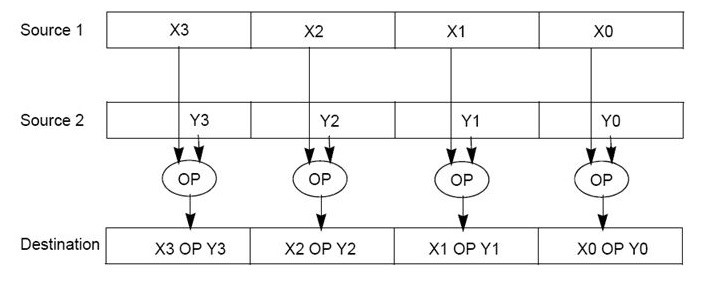

Now, consider the following sum of vectors, consisting of four separate additions for their corresponding components.

SIMD allows the CPU to execute four operations (denoted as OP in the image below) simultaneously in a single instruction. DirectXMath can leverage SIMD instructions (if supported by the CPU) to perform the same operation on the corresponding components of two XMVECTOR operands, as illustrated below.

However, __m128 variables require 16-byte alignment in memory. This isn’t an issue for global or local variables of this type, as the compiler automatically aligns them. Problems arise when using an XMVECTOR (which is an alias for __m128) as a member of a structure or class, where C++ packing rules might cause misalignment. To address this, DirectXMath provides specific types for including integer or floating-point vectors as class members without alignment concerns.

// 32-bit signed floating-point components

struct XMFLOAT2

{

float x;

float y;

};

struct XMFLOAT3

{

float x;

float y;

float z;

};

struct XMFLOAT4

{

float x;

float y;

float z;

float w;

};

// 32-bit signed integer components

struct XMINTT2

{

int x;

int y;

};

struct XMINT3

{

int x;

int y;

int z;

};

struct XMINT4

{

int x;

int y;

int z;

int w;

};

While these predefined types eliminate alignment concerns, they cannot be directly used in SIMD operations since they don’t map to XMM registers; they are simple C++ structure definitions. Therefore, for vector calculations, ensure conversion to XMVECTOR before proceeding. DirectXMath conveniently offers helper functions to facilitate the conversion from XMFLOAT to XMVECTOR,

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat2(const XMFLOAT2* pSource);

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat3(const XMFLOAT3* pSource);

XMVECTOR XMLoadFloat4(const XMFLOAT4* pSource);

and back from XMVECTOR to XMFLOAT (similar functions are defined for XMINT as well).

void XMStoreFloat2(XMFLOAT2* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);

void XMStoreFloat3(XMFLOAT3* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);

void XMStoreFloat4(XMFLOAT4* pDestination, FXMVECTOR V);

When you create a function that accepts one or more XMVECTORs, in declaring function parameters follow these guidelines:

Use FXMVECTOR for the first three parameters.

Use GXMVECTOR for the 4-th parameter.

Use HXMVECTOR for the 5-th and 6-th parameters.

Use CXMVECTOR for the remaining parameters.

Use XMVECTOR for output parameters.

See also

If the function is a C++ class constructor, then just use FXMVECTOR for the first three parameters and CXMVECTOR for the remaining ones.

FXMVECTOR, GXMVECTOR, HXMVECTOR and CXMVECTOR are all aliases to XMVECTOR. They allow the system to use the appropriate calling conventions for each platform supported by the DirectXMath Library. To learn more about calling convections, refer to the official documentation (see [Mica] and [Micb] in the reference list at the end of the tutorial).

As mentioned earlier, XMVECTOR is merely an alias for __m128, which corresponds to a type that maps to XMM registers. Consequently, using XMVECTORs to operate on vectors without using SIMD instructions is not recommended. Therefore, DirectXMath provides various helper functions utilizing SIMD instructions for both initializing and working with XMVECTORs. We’ll explore most of these functions in the upcoming tutorials.

For declaring vectorized constants (const **XMVECTOR), use XMVECTORF32 for floating-point values and XMVECTORU32 (or XMVECTORI32) for integer values. These types, defined as the union of a XMVECTOR and an array, enable convenient initialization syntax and let the compiler use SIMD instructions for other operations.

__declspec(align(16)) struct XMVECTORF32

{

union

{

float f[4];

XMVECTOR v;

};

inline operator XMVECTOR() const { return v; }

inline operator const float* () const { return f; }

};

static const XMVECTORF32 vZero = { 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f };

Support this project

If you found the content of this tutorial somewhat useful or interesting, please consider supporting this project by clicking on the Sponsor button below. Whether a small tip, a one-time donation, or a recurring payment, all contributions are welcome! Thank you!

References#

Gerald E. Farin and Dianne Hansford. Practical Linear Algebra: A Geometry Toolbox. CRC Press, 4th edition, 2021.

Microsoft. Directxmath library internals. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dxmath/pg-xnamath-internals.

Microsoft. __vectorcall. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/cpp/vectorcall.

Philip Schneider and David H. Eberly. Geometric Tools for Computer Graphics. Morgan Kaufmann, 1st edition, 2002.