Matrices#

Matrices are fundamental mathematical structures that play a crucial role in various fields, including mathematics, physics, engineering, and computer graphics as well. They provides a compact and efficient way to express transformations, such as scaling, rotation, and translation. This feature enables easy manipulation of the position, orientation, or size of 3D objects in a rendering scene in an easy way.

Definition#

Basically, a matrix is just a rectangular table of real numbers arranged in rows and columns.

The dimensions of a matrix are determined by the number of its rows and columns. For instance, an \(m\times n\) matrix consists of \(m\) rows and \(n\) columns. The individual numbers within a matrix are referred to as elements or entries. To indicate a specific entry within a matrix \(\mathbf{M}\), a double subscript notation, such as \(M_{ij}\), is often used to specify the element located in the i-th row and j-th column. Matrices are conventionally denoted using square brackets.

In computer graphics, it is common to work with square matrices \(n\times n\), where the number of rows and columns are equal. Row and column vectors, which are matrices with dimensions of \(1\times n\) and \(n\times 1\) respectively, are also widely used. When it comes to row and column vectors, a different naming convention is typically used: lowercase letters are used instead of uppercase ones. This is because row and column vectors can be used as operands in certain vector operations.

We can also use them to specify the rows or columns of a matrix. For example, we can write the following \(3\times 3\) matrix \(\mathbf{M}\) by using 3 row vectors, or 3 column vectors.

where \(\mathbf{u_i}=\left\lbrack\matrix{M_{i0}&M_{i1}&M_{i2}}\right\rbrack\), \(\ \mathbf{v_i}=\left\lbrack\matrix{M_{0i}&M_{1i}&M_{2i}}\right\rbrack\) and \(0\le i<3\).

For a more extensive and detailed presentation on vectors, you may find valuable information in [FH21] and [SE02].

Basic matrix operations#

There are several interesting operations that can be performed with matrices, including addition, subtraction, and two different types of multiplication.

Addition#

The addition of two matrices \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) can only be performed if the matrices have the same dimensions. If this condition is met, the corresponding elements of the matrices are added together.

The difference of two matrices is defined in a similar way.

Scalar multiplication#

We can multiply a matrix \(\mathbf{M}\) with a scalar \(k\) by scaling all the elements of the matrix by \(k\).

Properties of addition and scalar multiplications#

Since addition and scalar multiplication are performed element-wise on matrices, they inherit the following properties from real numbers:

Name |

Property |

|---|---|

Commutative |

\(\mathbf{A}+\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{B}+\mathbf{A}\) |

Associative |

\((\mathbf{A}+\mathbf{B})+\mathbf{C}=\mathbf{A}+(\mathbf{B}+\mathbf{C})\) |

Distributive (scalar) |

\((k+t)\mathbf{A} = k\mathbf{A}+t\mathbf{A}\) |

Distributive (matrix) |

\(k(\mathbf{A}+\mathbf{B}) = k\mathbf{A}+k\mathbf{B}\) |

Matrix multiplication#

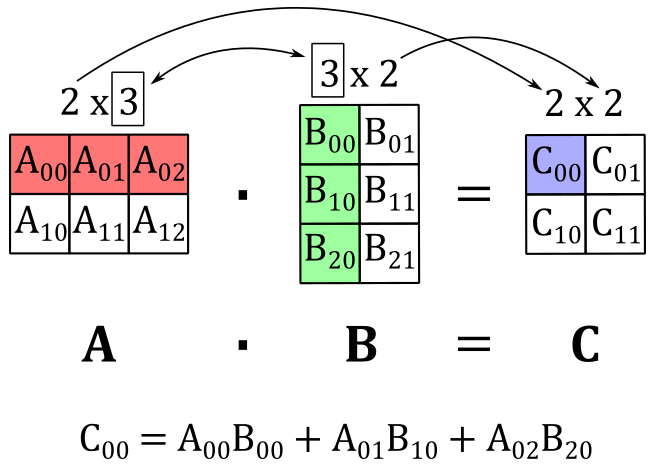

In order to multiply two matrices \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\), it is necessary for the number of columns in \(\mathbf{A}\) to be equal to the number of rows in \(\mathbf{B}\). This requirement arises because each element \(C_{ij}\) of the resulting matrix \(\mathbf{C}\) is obtained by taking the dot product of the i-th row of \(\mathbf{A}\) and the j-th column of \(\mathbf{B}\). This means that, if \(\mathbf{A}\) is an \(m\times n\) matrix and \(\mathbf{B}\) is an \(n\times p\) matrix, the resulting matrix \(\mathbf{C}\) will have dimensions \(m\times p\). This is because we need to multiply each of the \(m\) rows of \(\mathbf{A}\) by each of the \(p\) columns of \(\mathbf{B}\) in order to obtain all the elements of \(\mathbf{C}\). That is,

where \(\mathbf{A}_{i\ast}\) is the i-th row of \(\mathbf{A}\), and \(\mathbf{B}_{\ast j}\) is the j-th column of \(\mathbf{B}\).

As an example, the following illustration shows that if we multiply a \(2\times 3\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) by a \(3\times 2\) matrix \(\mathbf{B}\), we get a \(2\times 2\) matrix \(\mathbf{C}\) where the top-left element \(C_{00}\) is computed by taking the dot product of the 0-th row of \(\mathbf{A}\) and the 0-th column of \(\mathbf{B}\).

Observe that matrix multiplication is always defined for square matrices of the same dimension, and the resulting matrix will have the same dimensions as the operands.

Vector-Matrix multiplication#

A row vector is a \(1\times n\) matrix, so we can multiply it with a generic \(n\times p\) matrix. For example, if \(\mathbf{u}=(x, y, z)\) is a three-component vector that represent a row vector and \(\mathbf{A}\) is a \(3\times 3\) matrix, applying equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices1}\) we have that

The result is a row vector with three elements (just like \(\mathbf{u}\)) where each entry is the dot product of \(\mathbf{u}\) and a column of \(\mathbf{A}\). Now, if we actually perform the dot product we have

So, the vector-matrix multiplication can be seen as a sum of the rows of the matrix, scaled by the elements of the vector. This is an example of linear combination: a sum of vectors multiplied (scaled) by scalar coefficients. In this case, the vectors are the row vectors of the matrix, while the scalar coefficients are the elements of the vector acting as left operandin the multiplication. We can also write this linear combination as the product of a row vector and a column vector.

As you may easily notice, the multiplication of a row vector and a column vector is closely related to the concept of dot product. Indeed, we have that

That is, we can consider the operands of a dot product as row and column vectors, rather than just ordinary vectors.

What we have discussed so far in this section applies in general. That is, if we have a \(1\times n\) row vector \(\mathbf{u}\) and an \(n\times p\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), then the product \(\mathbf{uA}\) is a linear combination of the rows of \(\mathbf{A}\), with scalar coefficients given by the elements of \(\mathbf{u}\).

We can also multiply an \(m\times n\) matrix by an \(n\times 1\) column vector. For example, if \(\mathbf{A}\) is a \(3\times 3\) matrix and \(\mathbf{u}\) is a three-component vector that represent a column vector, we have that

The result is a column vector with three elements where each entry is the dot product of \(\mathbf{u}\) and a row of \(\mathbf{A}\). Now, if we perform the dot product we have

Therefore, the product of a matrix and a column vector is a linear combination of the columns of the matrix, scaled by the elements of the column vector.

Properties of matrix multiplication#

Since matrix multiplication is performed element-wise, it inherits the following properties from real numbers:

Name |

Property |

|---|---|

Associative |

\((\mathbf{AB})\mathbf{C}=\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{BC})\) |

Distributive |

\(\mathbf{A}(\mathbf{B}+\mathbf{C})=\mathbf{AB}+\mathbf{AC}\) |

The commutative property does not apply for two reasons. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, matrix multiplication is only defined when the number of columns in the left matrix is equal to the number of rows in the right matrix. Secondly, even with square matrices of the same dimension (where matrix multiplication is always defined), swapping the order of the operands can lead to a different resultant matrix ─ consider equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices1}\) and observe how each element of the resulting matrix is computed.

To conclude this section, as mentioned in Vectors, we stated that the cross product can be computed by multiplying a row vector by a matrix. We can now verify this statement using the following equation.

Also, it’s interesting to note that we can compute the orthogonal projection of a vector \(\mathbf{v}\) onto a unit vector \(\mathbf{n}\) by multiplying a row vector by a matrix.

Indeed, observe that the i-th component of \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\mathbf{n}\) is computed by multiplying \(n_i\) with \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\). For instance, the first component of \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\mathbf{n}\) is

As you can verify, the same result is obtained in the vector-matrix multiplication above by executing the dot product between \(\mathbf{v}\) and the first column of the matrix. The same applies to the other two components of \((\mathbf{v}\cdot\mathbf{n})\mathbf{n}\).

Transpose of a matrix#

The transpose of a matrix \(\mathbf{M}\) is often denoted with \(\mathbf{M}^T\). The transpose can be derived from the original matrix by simply interchanging its rows and columns.

As you can see, interchanging rows and columns in a matrix is equivalent to flipping the matrix over its diagonal. As a result, if we have a matrix \(\mathbf{M}\), obtaining the ij-th entry of its transpose can be achieved by simply swapping the subscripts and specifying the ji-th entry

Below are the properties of the matrix transpose.

\((\mathbf{A}^T)^T=\mathbf{A}\)

\((k\mathbf{A}^T)=k\mathbf{A}^T\)

\((\mathbf{A}+\mathbf{B})^T=\mathbf{A}^T+\mathbf{B}^T\)

\((\mathbf{AB})^T=\mathbf{B}^T\mathbf{A}^T\)

Proof

The first three properties are straightforward to prove. For the last property, we can demonstrate it by computing the ji-th entry of both \((\mathbf{AB})^T\) and \(\mathbf{B}^T\mathbf{A}^T\), and showing that they are equal. Specifically, we have:

The two expressions are the same since the dot product is commutative. Also, observe how we flipped the subscripts to refer to the corresponding entry in the transposes.

Identity matrix#

The identity matrix is a square matrix in which all the elements are zero, except for the entries on the main diagonal, which are all 1. The main diagonal consists of elements \(M_{ij}\) where \(i=j\).

The identity matrix is named as such because it serves as the multiplicative identity. That is, for an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{M}\) and an identity matrix \(\mathbf{I}\) of the same dimension, we have the following property:

Observe that the multiplication with the identity matrix is commutative by definition, meaning that the order of multiplication does not matter. This is an exception to the general operation of matrix multiplication, where the order of multiplication typically matters and matrix multiplication is not commutative.

Determinant of a matrix#

The determinant of a matrix is closely related to the concept of hypervolume, which represents the measure of length in 1D, area in 2D, and volume in 3D. It is important to note that the determinant is only defined for square matrices. Now, you may be wondering what it means to have a signed length, area, or volume. As mentioned earlier in this tutorial (and as we will formally demonstrate in a subsequent appendix), matrices are associated with transformations, and the sign of the determinant indicates whether a transformation preserves or reverses the orientation of the standard basis vectors. In simpler terms, when multiplying (transforming) the standard basis vectors \(\mathbf{i}\), \(\mathbf{j}\), and \(\mathbf{k}\) by a square matrix with a positive determinant, the handedness of the resulting coordinate system remains unchanged.

Before delving into the calculation of the determinant of a matrix, we first need to introduce the concept of matrix minors. By matrix minor of an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) we mean the \((n−1)\times(n−1)\) matrix \(\bar{\mathbf{A}}_{ij}\) derived from \(\mathbf{A}\) by deleting the i-th row and j-th column. For example,

Now, let’s see how to calculate the determinant \(\lvert\mathbf{A}\rvert\) (or \(det\mathbf{A}\)) of a square matrix \(\mathbf{A}\). First of all, the determinant of a \(1\times 1\) matrix is simply the only element in the matrix: \(\lvert\mathbf{A}\rvert=A_{00}\), where \(\mathbf{A}=\left\lbrack\matrix{A_{00}}\right\rbrack\). For matrices of higher dimensions, we can use the following recursive formula.

Observe that the dot in the equation above represents a scalar multiplication, not a dot product. The only variable in the equation is \(j\), allowing you to choose any \(i\)-th row of matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) and apply equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices2}\). Similarly, you can choose any \(j\)-th column of the matrix and apply equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices2}\) by changing the variable under the summation symbol to \(i\) instead of \(j\).

Equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices2}\) provides a recursive method for calculating the determinant of a matrix. It involves computing the determinants of matrix minors and using them in a linear combination, where the coefficients are the elements of the chosen i-th row. This approach allows us to extend the calculation of determinants from \(1\times 1\) matrices to \(2\times 2\) matrices by applying the formula above (we will use the elements of the first row of \(\mathbf{A}\) as coefficients; that is, we set \(i=0\)).

Now that we know how to calculate the determinants of \(2\times 2\) matrices, we can compute the determinants of \(3\times 3\) matrices as well.

As can be observed, the result obtained is similar to the outcome of the scalar triple product discussed in Vectors. This means that the determinant of a \(3\times 3\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) represents the signed volume of the parallelepiped formed by its three row vectors (or column vectors; indeed, note that \(\lvert\mathbf{A}\rvert\)=\(\lvert\mathbf{A}^T\rvert\)). Specifically, if the row vectors are denoted as \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\), \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{2\ast}\), the sign of the determinant is positive if the vectors \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) and \((\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\times\mathbf{A}_{2\ast})\) are on the same side (half-space) with respect to the plane defined by \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{2\ast}\). As will be further discussed in a later appendix, this property ensures that the handedness of a frame doesn’t change if we use \(\mathbf{A}\) to transform the standard basis vectors of the frame.

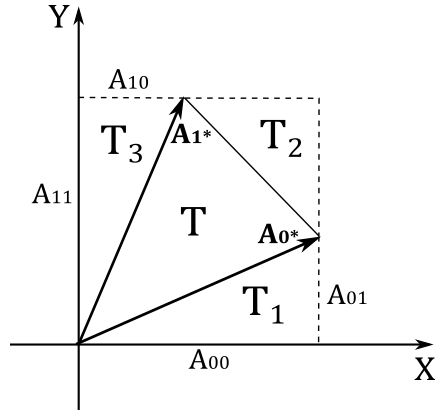

On the other hand, it’s much easier to prove that the determinant of a \(2\times 2\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) is the signed area of the parallelogram formed by its two row vectors \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\).

In the illustration above, we have that the area \(T\) of the triangle formed by \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\) is

where

Substituting and simplifying, we get

However, we want to calculate the area of the parallelogram \(A_p\) formed by \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\). For this purpose, we know that \(A_p=2T\), so we have that \(A_p\) is equal to equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices3}\), the determinant of a \(2\times 2\) matrix whose columns are \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) and \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\). If you can rotate \(\mathbf{A}_{0\ast}\) towards \(\mathbf{A}_{1\ast}\) in the same way as \(\mathbf{i}\) rotates towards \(\mathbf{j}\) then the area is positive, otherwise it is negative.

By now, you might have figured out how to compute the determinant of a \(4\times 4\) matrix.

It can be proven that if we add a scaled column (or row) of a matrix to another column (or row) of the same matrix, the determinant does not change. However, we won’t provide a formal proof here as a practical example is more than enough. Indeed, below you can verify that if we scale the second column of a simple \(2\times 2\) matrix by \(3\), and add the result to the first column, the determinant doesn’t change.

Adjoint of a matrix#

The cofactor \(C_{ij}\) of the entry \(A_{ij}\) in an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) can be defined as follows

Computing the cofactor of every element of the matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), we can create the cofactor matrix \(\mathbf{C}_\mathbf{A}\) of \(\mathbf{A}\), where \(C_{ij}\) is the element of \(\mathbf{C}_\mathbf{A}\) at the ij-th position.

The adjoint \(\mathbf{A}^\ast\) of the matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) is simply the transpose of its cofactor matrix: \(\mathbf{A}^\ast=\mathbf{C}_\mathbf{A}^T\). So, we have that the ij-th element of \(\mathbf{A}^\ast\) is

Please note the swap between subscripts in the matrix minor to select the corresponding entry in the transpose.

The adjoint of a matrix, and in particular the equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices4}\), is useful to compute the inverse of the matrix.

Inverse of a matrix#

In matrix algebra, the concept of inverse only applies to square matrices and is similar to the concept of inverse (or reciprocal) for real numbers. Specifically, for an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{M}\), its inverse \(\mathbf{M}^{-1}\) (which is still \(n\times n\)) can be computed as follows:

Just like with real numbers, if we multiply a matrix by its inverse we get the the multiplicative identity (in this case, an identity matrix of the same dimension). Observe that the inverse of \(\mathbf{M}^{-1}\) is \(\mathbf{M}\), so the commutative property applies by definition (this is the second exception to the general operation of matrix multiplication). A relevant difference from real numbers is that not every square matrix has an inverse. If the inverse \(\mathbf{M}^{-1}\) exists, it is unique and we say that \(\mathbf{M}\) is invertible, otherwise we call it singular. It can be proven that we can use equations \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices2}\) and \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices4}\) to compute the ij-th entry of the inverse \(\mathbf{A}^{-1}\) of a matrix \(\mathbf{A}\).

Example 1

Given a \(2\times 2\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) and its inverse \(\mathbf{A}^{-1}\)

Since \(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{A}^{-1}=\mathbf{I}\) we have that

From these two expressions, we can derive the following system of four equations with four unknowns \(v_{ij}\).

If we solve this system for \(v_{00}\) we get

That’s exactly the ratio between the cofactor of the 00-th element of \(\mathbf{A}\) and the its determinant. The same applies to the other unknowns and to matrices of higher dimensions as well, since it always ends up with a system of \(n\) equations with \(n\) unknowns.

As you may have noticed, in equation \(\eqref{eq:AMatrices5}\) we have a determinant in the denominator, which can be zero. This explains why not all square matrices have an inverse. Indeed, a matrix is invertible if its determinant is not zero.

Below are the properties of the matrix inverse.

\((\mathbf{A}^{-1})^T=(\mathbf{A}^T)^{-1}\)

\((\mathbf{AB})^{-1}=\mathbf{B}^{-1}\mathbf{A}^{-1}\)

Proof

For the first property, we need to show that \((\mathbf{A}^{-1})^T\) is the inverse of \(\mathbf{A}^T\). And indeed, from \((\mathbf{AB})^T=\mathbf{B}^T\mathbf{A}^T\) we have that

For the second property, assuming that \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) are square and invertible matrices, we need to show that \((\mathbf{AB})(\mathbf{B}^{-1}\mathbf{A}^{-1})=\mathbf{I}\) and \((\mathbf{B}^{-1}\mathbf{A}^{-1})(\mathbf{AB})=\mathbf{I}\). Indeed, using the associative property of matrix multiplication, we have that

Memory layout#

The elements of matrices used in C++ applications are stored contiguously row by row in CPU memory (RAM), as illustrated below.

We refer to this arrangement of elements as row-major order.

Of course, the elements of matrices used in shader code are stored contiguously in GPU memory as well. However, by default, they are considered as stored column by column. We refer to this arrangement as column-major order. Then, to represent the same matrix in shader code, its elements should have the following layout when stored in GPU heaps.

Now, a problem arises whenever we have to pass matrix data from our C++ applications to shader programs. As stated in a previous tutorial, the transfer of data from CPU to GPU is just a bit stream. Then, if we simply copy the matrix data from CPU memory to a GPU heap, the transpose of the matrix will be passed because the contiguous elements of the rows in CPU memory will be considered columns in GPU memory by the shader code.

Fortunately, we showed that \((\mathbf{A}^T)^T=\mathbf{A}\). Thismeans that we only need to transpose a matrix before passing it to the GPU in order to fix the problem. Another approach is to enforce a row-major order by indicating #pragma pack_matrix(row_major) at the start of a shader program. Alternatively, we can specify a row-major order for a single matrix by prefixing its declaration in the shader code with the keyword row_major. In the upcoming tutorials we will simply transpose the matrices in our C++ applications before passing them to the GPU. This way, we can work with matrices by using the default major orders both in C++ and HLSL.

To conclude this section, it’s interesting to see how we can use the intrinsic function mul (available in HLSL), which multiplies two operands using matrix math. The HLSL documentation describes the mul function as follows:

ret mul(x, y)

The x input value is a matrix. If x is a vector, it treated as a row vector.

The y input value is a matrix. If y is a vector, it treated as a column vector.The number of columns of x and the number of rows of y must be equal.

The result ret has the dimension (x-rows \(\times\) y-columns).

Now, if we want to multiply two matrices, or a vector and a matrix, what’s the best way to do it using the mul function? Let’s assume we are using a column-major order in the shader code.

If you want to multiply two \(n\times n\) matrices \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{B}\), then we transpose them in the C++ code before passing the matrix data to the GPU. At that point, in the HLSL code, we simply pass \(\mathbf{A}\) as the first argument and \(\mathbf{B}\) as the second argument of mul, which will return a matrix where each element is the dot product of a row of \(\mathbf{A}\) with a column of \(\mathbf{B}\).

On the other hand, what happens if you want to multiply a vector and a matrix? Well, it depends on how you want to perform this operation. If you want to multiply the row vector by each column of the matrix, then you should pass the row vector as the first argument, and the transpose of the matrix as the second argument to mul. Indeed, after copying the transpose of the matrix in a GPU heap, the layout of its elements in memory will be

Therefore, the columns can be easily loaded into shader core registers since their entries are contiguous in memory.

The row vector is loaded in a register as well.

At that point, the GPU can simply compute the dot product of \(reg_0\) with the other registers to compute the four elements of the resultant vector.

Under the same conditions, if you want to multiply a column vector by each row of the matrix, then you can pass the transpose of the matrix as the first argument, and the vector as the second argument to mul. At that point, the GPU may have to execute more instructions to perform the dot product of the vector with the rows of the matrix since the elements of the matrix are ordered column by column. The conditional is used because the real GPU instructions (not the bytecode) could be similar in both cases. The following listings show both the bytecode and a possible translation in GPU machine code of the multiplication between a vector (vpos) and a matrix (World), passed as arguments to mul.

# BYTECODE (DXBC\DXIL)

# output.position = mul(vpos, World);

dp4 r0.x, v0.xyzw, World[0].xyzw # dot product of vpos with the 1st column of World

dp4 r0.y, v0.xyzw, World[1].xyzw # dot product of vpos with the 2nd column of World

dp4 r0.z, v0.xyzw, World[2].xyzw # dot product of vpos with the 3rd column of World

dp4 r0.w, v0.xyzw, World[3].xyzw # dot product of vpos with the 4th column of World

# BYTECODE (DXBC\DXIL)

# output.position = mul(World, vpos);

mul r0.xyzw, v0.xxxx, World[0].xyzw # scale the 1st column of World by vpos.x and put the result in r0

mul r1.xyzw, v0.yyyy, World[1].xyzw # scale the 2st column of World by vpos.y and put the result in r1

add r0.xyzw, r0.xyzw, r1.xyzw # r0 += r1; sum of the first 2 addends

mul r1.xyzw, v0.zzzz, World[2].xyzw # scale the 3rd column of World by vpos.z and put the result in r1

add r0.xyzw, r0.xyzw, r1.xyzw # r0 += r1; add the third addend

mul r1.xyzw, v0.wwww, World[3].xyzw # scale the 4th column of World by vpos.z and put the result in r1

add r0.xyzw, r0.xyzw, r1.xyzw # r0 += r1; add the fourth addend

# ISA Disassembly

# output.position = mul(vpos, World);

v_mul_f32 v0, s0, v4 # 000000000018: 0A000800 v0 = ax

v_mul_f32 v1, s4, v4 # 00000000001C: 0A020804 v1 = bx

v_mul_f32 v2, s8, v4 # 000000000020: 0A040808 v2 = cx

v_mul_f32 v3, s12, v4 # 000000000024: 0A06080C v3 = dx

v_mac_f32 v0, s1, v5 # 000000000028: 2C000A01 v0 = ey + ax

v_mac_f32 v1, s5, v5 # 00000000002C: 2C020A05 v1 = fy + bx

v_mac_f32 v2, s9, v5 # 000000000030: 2C040A09 v2 = gy + cx

v_mac_f32 v3, s13, v5 # 000000000034: 2C060A0D v3 = hy + dx

v_mac_f32 v0, s2, v6 # 000000000038: 2C000C02 v0 = iz + ey + ax

v_mac_f32 v1, s6, v6 # 00000000003C: 2C020C06 v1 = jz + fy + bx

v_mac_f32 v2, s10, v6 # 000000000040: 2C040C0A v2 = kz + gy + cx

v_mac_f32 v3, s14, v6 # 000000000044: 2C060C0E v3 = lz + hy + dx

v_mac_f32 v0, s3, v7 # 000000000048: 2C000E03 v0 = mw + iz + ey + ax

v_mac_f32 v1, s7, v7 # 00000000004C: 2C020E07 v1 = nw + jz + fy + bx

v_mac_f32 v2, s11, v7 # 000000000050: 2C040E0B v2 = ow + kz + gy + cx

v_mac_f32 v3, s15, v7 # 000000000054: 2C060E0F v3 = pw + lz + hy + dx

exp pos0, v0, v1, v2, v3 done # 000000000058: C40008CF 03020100 output.position = {v0, v1, v2, v3}

# ISA Disassembly

# output.position = mul(World, vpos);

v_mul_f32 v0, s4, v5 # 000000000018: 0A000A04 v0 = by

v_mul_f32 v1, s5, v5 # 00000000001C: 0A020A05 v1 = fy

v_mul_f32 v2, s6, v5 # 000000000020: 0A040A06 v2 = jy

v_mul_f32 v3, s7, v5 # 000000000024: 0A060A07 v3 = ny

v_mac_f32 v0, s0, v4 # 000000000028: 2C000800 v0 = ax + by

v_mac_f32 v1, s1, v4 # 00000000002C: 2C020801 v1 = ex + fy

v_mac_f32 v2, s2, v4 # 000000000030: 2C040802 v2 = ix + jy

v_mac_f32 v3, s3, v4 # 000000000034: 2C060803 v3 = mx + ny

v_mac_f32 v0, s8, v6 # 000000000038: 2C000C08 v0 = cz + ax + by

v_mac_f32 v1, s9, v6 # 00000000003C: 2C020C09 v1 = gz + ex + fy

v_mac_f32 v2, s10, v6 # 000000000040: 2C040C0A v2 = kz + ix + jy

v_mac_f32 v3, s11, v6 # 000000000044: 2C060C0B v3 = oz + mx + ny

v_mac_f32 v0, s12, v7 # 000000000048: 2C000E0C v0 = dw + cz + ax + by

v_mac_f32 v1, s13, v7 # 00000000004C: 2C020E0D v1 = hw + gz + ex + fy

v_mac_f32 v2, s14, v7 # 000000000050: 2C040E0E v2 = lw + kz + ix + jy

v_mac_f32 v3, s15, v7 # 000000000054: 2C060E0F v3 = pw + oz + mx + ny

exp pos0, v0, v1, v2, v3 done # 000000000058: C40008CF 03020100 output.position = {v0, v1, v2, v3}

Aside from the registers used, the GPU machine code (ISA disassembly) is the same for both vector by matrix and matrix by vector multiplications. To understand the listings above, observe how we compute the multiplication of a row vector by a matrix.

And the multiplication of a matrix by a column vector as well.

In the latter case, observe that the first column of the matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) is scaled by \(x\), the second by \(y\), the third by \(z\), and the fourth by \(w\). Finally, the sum of corresponding components in the scaled columns gives us the components of the resultant vector.

Important

The ISA disassembly unveils what GPUs mean by SIMD operations. GPU hardware cores commonly include 32-bit registers and ALUs to execute single operations on 32-bit data. However, GPUs are perfectly capable of performing the same instruction in parallel on different hardware cores (usually 64) for different data (e.g., vertex data). The shader model hides\abstracts these hardware details with 128-bit shader registers and SIMD instructions to mimic the CPU behaviour. We will return to the architecture and design of GPUs in a later tutorial.

Matrices in DirectX#

Matrices play a crucial role in computer graphics, making them a fundamental tool to use in DirectX applications as well. They are widely used in both C++ and in HLSL.

HLSL#

In HLSL, we can use the built-in types float2x2, float3x3 and float4x4 to represent \(2\times 2\), \(3\times 3\) and \(4\times 4\) matrices of floating-point elements. Similarly, we can use int2x2, int3x3 and int4x4 for matrices of integers. We can also use the keyword matrix to declare matrices of various types and dimensions. To access a specific element of a matrix we can use array notation (indexing), or the structure operator ., followed by one of two naming sets:

The zero-based row-column position:

_m00, _m01, _m02, _m03

_m10, _m11, _m12, _m13

_m20, _m21, _m22, _m23

_m30, _m31, _m32, _m33

The one-based row-column position:

_11, _12, _13, _14

_21, _22, _23, _24

_31, _32, _33, _34

_41, _42, _43, _44

Just like vectors, we can specify one or more components from either naming set. However, we cannot use swizzling with array notation.

As you can see in the following listing, initialization and indexing always work with rows, even if we use a column-major order in HLSL. That way, we can mimic the usual C++ style to access matrix elements from HLSL code.

// float2x2 fMatrix = {0.0f, 0.1f,2.1f, 2.2f};

matrix<float, 2, 2> fMatrix =

{

0.0f, 0.1f, // row 1

2.1f, 2.2f // row 2

};

float4x4 M;

M = { // Initialize M

1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f, // first row

5.0f, 6.0f, 7.0f, 8.0f, // second row

// ... // third row

// ... // fourth row

};

// Initialize T

// {0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f} first row

// {1.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f} second row

// {2.0f, 2.0f, 2.0f} third row

float3x3 T = { { 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f }, { 1.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f }, { 2.0f, 2.0f, 2.0f } };

float4 v = { 4.0f, 3.0f, 2.0f, 1.0f };

float f0 = M[0][1]; // f0 = 0|1-th element of M

float f1 = M._m01; // equivalent to f1 = M[0][1]

float f2 = M._12; // equivalent to f2 = M[0][1]

M[0] = v; // First row of M = v

M._m11 = v[0]; // equivalent to M[1][1] = v[0]

float4 f3 = M._11_12; // equivalent to f3 = (M[0][0], M[0][1])

M._12_21 = M._21_12; // equivalent to the following pseudocode:

// float2 vec = (M[0][1], M[1][0])

// vec = vec.yx

C++#

In C++, we can use the XMMATRIX type provided by DirectXMath to represent \(4\times 4\) matrices. If you need matrices of lower dimensions, you can use XMMATRIX as well by only initializing and using the corresponding elements.

__declspec(align(16)) struct XMMATRIX

{

XMVECTOR r[4];

XMMATRIX() XM_CTOR_DEFAULT

constexpr XMMATRIX(FXMVECTOR R0, FXMVECTOR R1, FXMVECTOR R2, CXMVECTOR R3) :

r{ R0,R1,R2,R3 } {}

XMMATRIX(float m00, float m01, float m02, float m03,

float m10, float m11, float m12, float m13,

float m20, float m21, float m22, float m23,

float m30, float m31, float m32, float m33);

explicit XMMATRIX(_In_reads_(16) const float* pArray);

XMMATRIX& operator= (const XMMATRIX& M)

{

r[0] = M.r[0]; r[1] = M.r[1]; r[2] = M.r[2]; r[3] = M.r[3]; return *this;

}

XMMATRIX operator+ () const { return *this; }

XMMATRIX operator- () const;

XMMATRIX& operator+= (FXMMATRIX M);

XMMATRIX& operator-= (FXMMATRIX M);

XMMATRIX& operator*= (FXMMATRIX M);

XMMATRIX& operator*= (float S);

XMMATRIX& operator/= (float S);

XMMATRIX operator+ (FXMMATRIX M) const;

XMMATRIX operator- (FXMMATRIX M) const;

XMMATRIX operator* (FXMMATRIX M) const;

XMMATRIX operator* (float S) const;

XMMATRIX operator/ (float S) const;

friend XMMATRIX operator* (float S, FXMMATRIX M);

};

As you can see, XMMATRIX includes an array of XMVECTORs, so we shouldn’t use it as a class member. Fortunately, DirectXMath also provides the following types, which allow us to use matrices as class members.

struct XMFLOAT4X4

{

union

{

struct

{

float _11, _12, _13, _14;

float _21, _22, _23, _24;

float _31, _32, _33, _34;

float _41, _42, _43, _44;

};

float m[4][4];

};

XMFLOAT4X4() XM_CTOR_DEFAULT

XM_CONSTEXPR XMFLOAT4X4(float m00, float m01, float m02, float m03,

float m10, float m11, float m12, float m13,

float m20, float m21, float m22, float m23,

float m30, float m31, float m32, float m33)

: _11(m00), _12(m01), _13(m02), _14(m03),

_21(m10), _22(m11), _23(m12), _24(m13),

_31(m20), _32(m21), _33(m22), _34(m23),

_41(m30), _42(m31), _43(m32), _44(m33) {}

explicit XMFLOAT4X4(_In_reads_(16) const float* pArray);

float operator() (size_t Row, size_t Column) const { return m[Row][Column]; }

float& operator() (size_t Row, size_t Column) { return m[Row][Column]; }

XMFLOAT4X4& operator= (const XMFLOAT4X4& Float4x4);

};

struct XMFLOAT3X3

{

union

{

struct

{

float _11, _12, _13;

float _21, _22, _23;

float _31, _32, _33;

};

float m[3][3];

};

XMFLOAT3X3() XM_CTOR_DEFAULT

XM_CONSTEXPR XMFLOAT3X3(float m00, float m01, float m02,

float m10, float m11, float m12,

float m20, float m21, float m22)

: _11(m00), _12(m01), _13(m02),

_21(m10), _22(m11), _23(m12),

_31(m20), _32(m21), _33(m22) {}

explicit XMFLOAT3X3(_In_reads_(9) const float* pArray);

float operator() (size_t Row, size_t Column) const { return m[Row][Column]; }

float& operator() (size_t Row, size_t Column) { return m[Row][Column]; }

XMFLOAT3X3& operator= (const XMFLOAT3X3& Float3x3);

};

When you create a function that accepts one or more XMMATRIXs, in declaring function parameters follow these guidelines:

Use FXMMATRIX for the first parameter.

Use CXMMATRIX for the remaining ones.

FXMMATRIX and CXMMATRIX are both aliases to XMVECTOR. They allow the system to use the appropriate calling conventions for each platform supported by the DirectXMath Library. To learn more about calling convections, refer to the official documentation (see [Mica] and [Micb] in the reference list at the end of the tutorial).

Obviously, all the basic matrix operations discussed in this tutorial (sum, difference, and various types of multiplication) are defined in HLSL using the usual operators (+, -, *). Fortunately, DirectXMath overloads these same operators for matrices to allow us to perform the same operations in C++.

DirectXMath also provides many helper functions to work with matrices, enabling us to perform useful operations such as inversion, transposition, and determinant calculation. We will encounter and use most of these functions in the upcoming tutorials.

Support this project

If you found the content of this tutorial somewhat useful or interesting, please consider supporting this project by clicking on the Sponsor button below. Whether a small tip, a one-time donation, or a recurring payment, all contributions are welcome! Thank you!

References#

Gerald E. Farin and Dianne Hansford. Practical Linear Algebra: A Geometry Toolbox. CRC Press, 4th edition, 2021.

Microsoft. Directxmath library internals. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/dxmath/pg-xnamath-internals.

Microsoft. __vectorcall. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/cpp/vectorcall.

Philip Schneider and David H. Eberly. Geometric Tools for Computer Graphics. Morgan Kaufmann, 1st edition, 2002.