Spaces#

The magic of computer graphics lies in the ability to transform and manipulate objects within cartesian coordinate systems, also known as spaces for brevity. Indeed, a fundamental concept that forms the backbone of many graphics pipelines is the transformation of 3D objects to represent them in various spaces in order to bring virtual scene to be shown on the screen.

In Transformations, we showed that to transform a points and vectors we can transform the basis vectors representing the starting frame, so that we can express the coordinates with respect to a new space. Building upon this foundation, it’s now interesting to look at the common spaces typically employed in the graphics pipeline and how to go from a space to another as well in order to project the 3D scenes onto a 2D surface before showing the result on the screen.

From the initial local space where each object is defined, to the all-encompassing world space, and the camera space that offers a unique perspective, each space plays a crucial role in the intricate process of rendering. For a more extensive and detailed presentation on spaces used in computer graphics and transformations to go from one space to another, you may find valuable information in [MS22].

Object space#

The object space, also known as local space, is the frame in which 3D objects\meshes are defined. When creating 3D objects, graphic artists often work in a convenient space that simplifies vertex modeling by providing symmetry with respect to the origin of the coordinate system.

For instance, consider the modeling of a sphere. It is much easier to place all the vertices at an equal distance from the origin, rather than using a random point as the sphere’s center. This intuitive choice is not only practical but can also be mathematically justified.

Note

The local space is the frame where the vertices of a mesh are defined in the first place. These vertices are often stored in a file on disk and can be loaded into memory to create the vertex buffer, which is subsequently sent to the input assembler. Within this buffer, the vertices remain in their local space representation until the graphics pipeline performs the necessary transformations to convert the 3D objects they represent into a 2D representation to show on the screen.

Note

Throughout this tutorial series, we’ll use a left-handed coordinate system where the y-axis points upwards to represent the object space. As explained in Vectors, this is completely arbitrary and you can choose any configuration (z-up or y-up) and handedness that suits your needs.

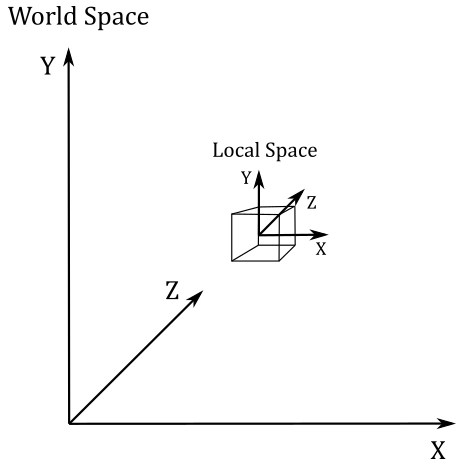

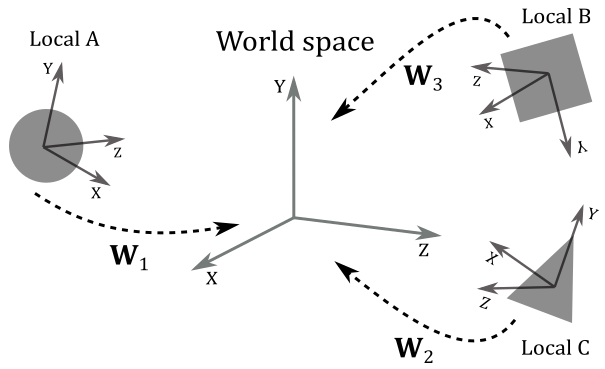

World space and World matrix#

When the input assembler sends its output to the next stage (the vertex shader), we have vertices in local space that we want to place in a 3D global scene shared by all objects. The space of the global scene is called world space, and the transformation to go from local to world space is called world transformation. To represent the world space, we will use the same convention as the object space: left-handed system with the y-axis pointing upwards.

As we know, to go from a frame to another, we need to express the basis vectors of the starting frame with respect to the new frame. So, we can build a matrix \(\mathbf{W}=\mathbf{SRT}\) (a composition of three trasformations: a scaling, a rotation, and a translation) associated with the world transformation we want to apply to the local frame to get the coordinates of its basis vectors with respect to the world space. Therefore, \(\mathbf{W}\) is the matrix to go from local to world space, and that allows us to put an object (or rather, its vertices) in the global scene. For this reason, we call \(\mathbf{W}\) the world matrix.

Important

We hardly place every object in the same location of the world space, so \(\mathbf{W}\) will likely be different from object to object.

Thus, we can define \(\mathbf{W}\) as

where the first three rows of \(\mathbf{W}\) are the scaled and rotated basis vectors of the local space with respect to the world space, while the last row is the translation of the origin of the local space (again, with respect to the world space).

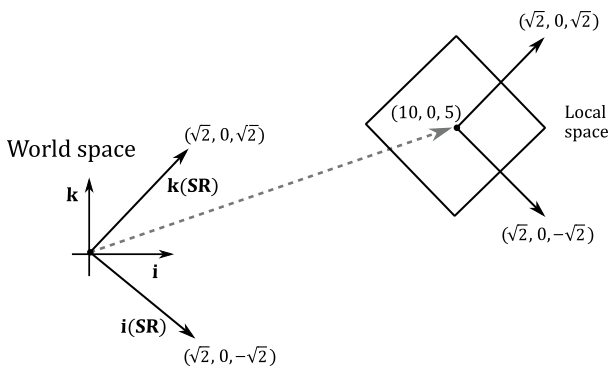

Example 4

Given a cube in local space, suppose you want to double its size, rotate it by \(45°\) clockwise about the y-axis, and move it at \((10,0,5)\) in the world space. Therefore, we must transform all the vertices of the cube using the following world matrix:

The image below shows a 2D cross-section of the scene, obtained by looking down along the positive y-axis. Note that the first three rows of the \(\mathbf{W}\) matrix are the scaled and rotated basis vectors of the local space in world coordinates (that is, whose coordinates are with respect to the world space), while the fourth row is the position (point) of the origin of the translated local space (again, in world coordinates). Based on the information provided in Matrices, we can use \(\mathbf{W}\) to transform the vertices of the cube in order to place it in the global scene.

View space and View matrix#

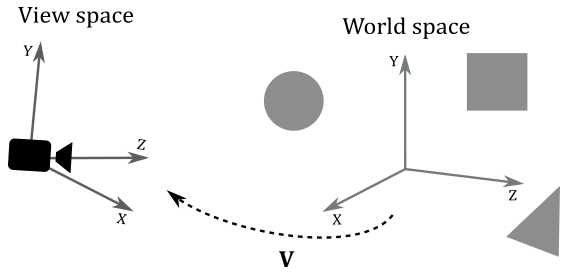

Once we apply the world transformation, all objects are in world space. However, we still require a specific viewpoint to observe the 3D scene. This space is typically called view space, or camera space, and to represent it, we’ll adopt a left-handed system similar to the ones used for local and world spaces, where the y-axis points upwards. To transition objects from world space to view space, we need to apply another transformation: the view transformation. This involves applying a view matrix (denoted by \(\mathbf{V}\)), which configures the camera’s position, orientation, and perspective within the global scene. By applying the view matrix, we effectively convert the coordinates of objects’ vertices from world space to view space, establishing the desired viewpoint for our 3D scene.

Unlike the world transformation, where each object typically requires a separate transformation, the view transformation usually employs the same view matrix for all objects in the global scene. This is because we generally aim for a consistent viewpoint to observe the entire 3D scene. In other words, it’s as if we can consider the entire scene, encompassing all the objects, as a single large object that needs to be transformed from world space to view space.

Now, to build the view matrix, we can start considering the camera as an ordinary object we can place in world space. So, we can use a world matrix \(\mathbf{W}_c\) to put the camera in the global space as the point of view from which to look at the scene.

\(\mathbf{W}_c\) is the matrix that transforms from the local space of the camera to the world space. However, note that the local space of the camera is exactly the view space, the perspective from which we observe the scene. This means that \(\mathbf{W}_c\) is the matrix for transitioning from view space to world space. Therefore, we can simply compute the inverse \(\mathbf{W}_c^{-1}\) to get the view matrix allowing to go from world space to view space. In this case, computing the inverse is straightforward as \(\mathbf{W}_c\) is the composition of a rotation and a translation: \(\mathbf{W}_c=\mathbf{RT}\). Indeed, it doesn’t make any sense to scale the camera since it’s a dummy object; we are only interested in the position and orientation of the view space. And we don’t need scaling in the inverse transformation either, as we’ve already scaled the objects during the world transformations, aiming to maintain their size in world space. Therefore, the first three rows of \(\mathbf{W}_c\) represent the rotations of the standard basis vectors of the view space relative to the world space (that is, in world coordinates), while the last row represents the position of the origin of the view space, in world coordinates as well. So, we have

Indeed, remember that the inverse of a rotation matrix is equivalent to its transpose (as explained in Matrices). Consequently, the view matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) to go from world space to view space is

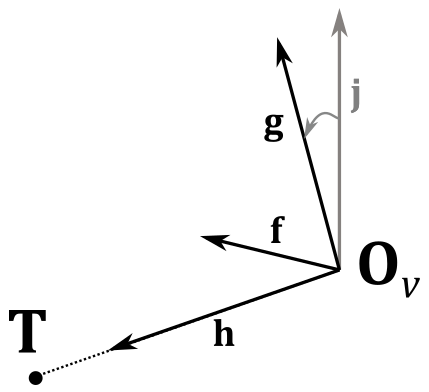

It’s interesting to note that, since \(\mathbf{f}\), \(\mathbf{g}\), \(\mathbf{h}\) and \(\mathbf{t}\) are all in world coordinates, we can compute the view matrix \(\mathbf{V}\) from scratch by only using two points in the world space: the origin \(\mathbf{O}_v\) of the view space and a target point \(\mathbf{T}\) indicating where the camera is aimed. To verify this, let’s start by observing that

because both \(\mathbf{O}_v\) and \(\mathbf{t}\) represent the same geometric entity: the position of the view space in world coordinates.

Now, we need to calculate \(\mathbf{f}\), \(\mathbf{g}\) and \(\mathbf{h}\), which represent the transformations of the standard basis vectors \(\mathbf{i}\), \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{k}\) in the camera’s local space. Specifically, \(\mathbf{h}\), the transformation of \(\mathbf{k}\), points in the direction the camera is aimed (z-axis of the camera space in the image above). Therefore, we can calculate it simply by taking the difference between \(\mathbf{T}\) and \(\mathbf{O}_v\).

Observe that since this is the difference between two points in world coordinates, the result is a vector in world coordinates as well.

To compute \(\mathbf{f}\) (transformation of \(\mathbf{i}\)), we will use \(\mathbf{j}\), the unit vector we chose pointing upwards in local, world and camera spaces. This is because we typically limit the vertical rotation of the camera to less than \(90°\) around the x-axis (the reasons behind this will be explained in another tutorial). As a result, the angle between \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{g}\) will be less than \(90°\). Similarly, the angle between \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{h}\) will be less than \(180°\), as \(\mathbf{g}\) and \(\mathbf{h}\) must be orthogonal to each other.

Therefore, we can calculate \(\mathbf{f}\) with the following cross product.

As explained above, the vector \(\mathbf{j}\) remains consistent regardless the frame of reference (i.e., it has the same coordinates \((0,1,0)\) in both local and world spaces). Therefore, both \(\mathbf{j}\) and \(\mathbf{h}\) can be considered as expressed relative to the world space, which we defined as a left-handed system. This implies that the direction of \(\mathbf{f}\) will be the one that sees \(\mathbf{j}\) rotate clockwise towards \(\mathbf{h}\), making \(\mathbf{f}\), \(\mathbf{j}\), and \(\mathbf{h}\) a left-handed system. This is exactly the expected result when transitioning from world space to view space, as we usually don’t want to change the handedness of the system we are working with after a transformation.

Finally, to compute \(\mathbf{g}\) (transformation of \(\mathbf{j}\)), we can simply calculate the cross product between \(\mathbf{h}\) and \(\mathbf{f}\).

Note

Both \(\mathbf{f}\) and \(\mathbf{h}\) are unit vectors, so we don’t need to normalize the result. Recall what we stated in Vectors: the length of the vector resulting from the cross product \(\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\) is \(\vert\mathbf{u}\times\mathbf{v}\vert=\vert\mathbf{u}\vert\vert\mathbf{v}\vert\sin{\theta}\). In this case, we have \(\vert\mathbf{h}\vert=\vert\mathbf{f}\vert=1\) and \(\sin{90°}=1\).

View matrix in DirectX#

DirectXMath provides the helper function XMMatrixLookAtLH to build a view matrix similar to the one we discussed in this section (i.e., for transitioning from world to camera spaces defined as left-handed systems). You need to pass the camera position and target point as arguments to this function, which returns the related view matrix.

// pos: position (in world coordinates) of the (origin of the) view space.

// target: position (in world coordinates) where we want the camera is aimed at.

// up == j (unit basis vector which points up).

XMVECTOR pos = XMVectorSet(x, y, z, 1.0f);

XMVECTOR target = XMVectorZero();

XMVECTOR up = XMVectorSet(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f);

// Compute the View matrix.

XMMATRIX V = XMMatrixLookAtLH(pos, target, up);

XMVectorSet and XMVectorZero are also helper functions. They allow us to initialize an XMVECTOR variable using a single SIMD instruction (if SIMD instructions are supported by the CPU).

Note

As explained in Vectors, XMVECTOR is an alias for __m128, so we should avoid initializing it with a simple assignment or the usual array initialization, because these methods may require multiple instructions, which is inefficient. Instead, XMVectorSet and XMVectorZero offer a dual implementation (No-Intrinsics and SSE-Intrinsics, as detailed in Transformations) that allows the CPU to leverage SIMD instructions (if supported) to load four values into a 16-byte aligned __m128 variable in a single instruction, significantly improving performance.

The implementation of the XMMatrixLookAtLH function should be relatively straightforward to understand, given the concepts we have discussed in this section and in Transformations.

inline XMMATRIX XM_CALLCONV XMMatrixLookAtLH

(

FXMVECTOR EyePosition,

FXMVECTOR FocusPosition,

FXMVECTOR UpDirection

) noexcept

{

XMVECTOR EyeDirection = XMVectorSubtract(FocusPosition, EyePosition);

return XMMatrixLookToLH(EyePosition, EyeDirection, UpDirection);

}

inline XMMATRIX XM_CALLCONV XMMatrixLookToLH

(

FXMVECTOR EyePosition,

FXMVECTOR EyeDirection,

FXMVECTOR UpDirection

) noexcept

{

assert(!XMVector3Equal(EyeDirection, XMVectorZero()));

assert(!XMVector3IsInfinite(EyeDirection));

assert(!XMVector3Equal(UpDirection, XMVectorZero()));

assert(!XMVector3IsInfinite(UpDirection));

XMVECTOR R2 = XMVector3Normalize(EyeDirection);

XMVECTOR R0 = XMVector3Cross(UpDirection, R2);

R0 = XMVector3Normalize(R0);

XMVECTOR R1 = XMVector3Cross(R2, R0);

XMVECTOR NegEyePosition = XMVectorNegate(EyePosition);

XMVECTOR D0 = XMVector3Dot(R0, NegEyePosition);

XMVECTOR D1 = XMVector3Dot(R1, NegEyePosition);

XMVECTOR D2 = XMVector3Dot(R2, NegEyePosition);

XMMATRIX M;

M.r[0] = XMVectorSelect(D0, R0, g_XMSelect1110.v);

M.r[1] = XMVectorSelect(D1, R1, g_XMSelect1110.v);

M.r[2] = XMVectorSelect(D2, R2, g_XMSelect1110.v);

M.r[3] = g_XMIdentityR3.v;

M = XMMatrixTranspose(M);

return M;

}

EyePosition, FocusPosition and UpDirection are the origin, target and up direction of the camera, expressed in world coordinates.

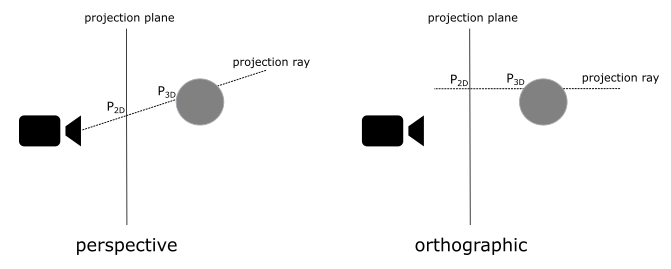

NDC space and Projection matrix#

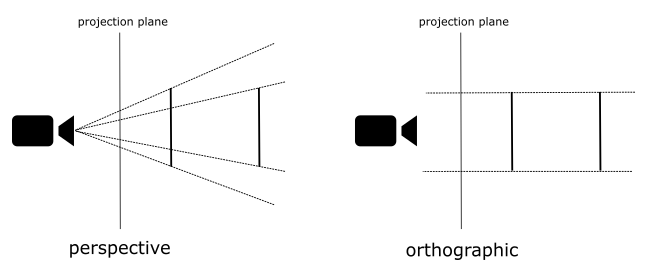

Once we have all objects in camera space, the next step is to project them onto a plane to obtain a 2D representation of the 3D scene. To achieve this, we can ideally place a plane in front of the camera and trace rays from the camera to each vertex of the mesh, as illustrated in the image below. The intersection between these rays and the plane gives us a 2D representation of the corresponding 3D vertices. Note that if the projection rays are parallel to each other and orthogonal to the projection plane, the camera’s position becomes irrelevant.

In the first case, where the projection rays converge towards a focal point, distant objects appear smaller. This replicates the way human vision works in real life and we commonly refer to this type of projection as perspective.

On the other hand, if the projection rays are parallel to each other, the perspective effect is lost, and the size of objects becomes independent of their distance from the camera. This type of projection is known as orthographic.

To better understand the difference, consider the illustration provided below. It depicts two segments of equal size placed at different distances from the camera. In the perspective projection, the closer segment appears longer when projected onto the projection plane, emphasizing the depth perception effect.

Fortunately, the intricacies of the projection process are almost transparent to the programmer, who is primarily responsible for defining the portion of the 3D scene to be projected onto the projection plane. Indeed, in most cases, capturing the entire scene is not necessary or desired. Depending on the type of projection being used, different bounding geometries define the region of interest.

In orthographic projections, the region of interest is represented by a box. This box encompasses the portion of the scene that will be projected onto the 2D plane. While we can use any plane in front of the camera as the projection plane, typically the box face closest to the camera is used as the projection window where the 3D scene is projected.

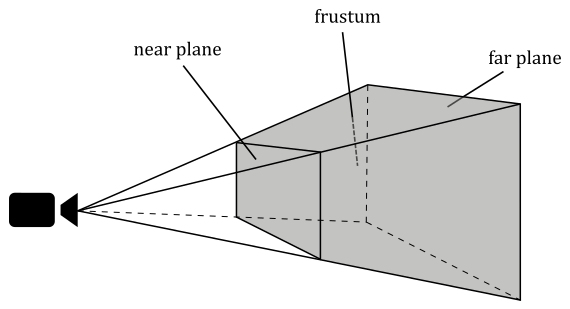

In perspective projections, the region of interest is defined by a frustum. A frustum is the volume enclosed between two parallel planes that intersect a pyramid. The apex of the pyramid corresponds to the camera’s position. The plane closer to the camera is called the near plane, while the farther plane is called the far plane. We can obtain a projection window by intersecting the pyramid between the camera and the near plane, with another plane parallel to the near one. Alternatively, the upper face of the frustum, the intersection between the near plane and the pyramid, can also be used as the projection window. In computer graphics literature, the terms “near plane” and “far plane” are commonly used to refer to the corresponding windows as well.

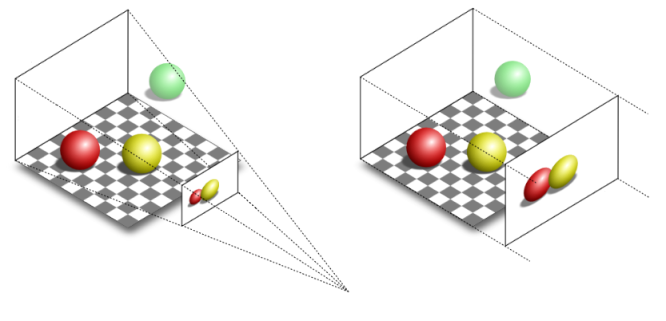

The illustration below clearly demonstrates the differences between perspective and orthographic projections. In both projections, the green ball lies outside the defined region of interest and therefore is not projected onto the projection window.

In the orthographic projection, the red and yellow balls appear the same size, regardless of their distance from the camera. This is because the projection rays are parallel and do not converge towards a focal point, resulting in a lack of perspective distortion.

On the other hand, in the perspective projection, the red ball appears smaller compared to the yellow ball. This is due to the converging projection rays that mimic the behavior of human vision in real life. As objects move further away from the camera, they appear smaller, resulting in the size difference observed in the perspective projection.

To define a frustum (for perspective projections) or a box (for orthographic projections), we need to specify the distances from the camera to the near and far planes. For convenience, we typically define this bounding geometry in view space, where the camera position is located at the origin. Additionally, we need to determine the dimensions of the projection window. With this information, we can construct a projection matrix. This matrix transforms 3D vertices from view space to a space called Normalized Device Coordinates (NDC).

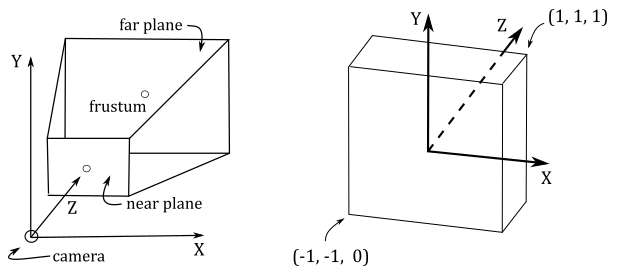

In perspective projection, the frustum defined in view space becomes a box in NDC space. The origin of this box is located at the center of its front face, which corresponds to the transformed near plane\window. A significant aspect of interest is that the objects contained within the box in NDC space (previously within the frustum\box in view space) will have vertex coordinates falling within the following ranges:

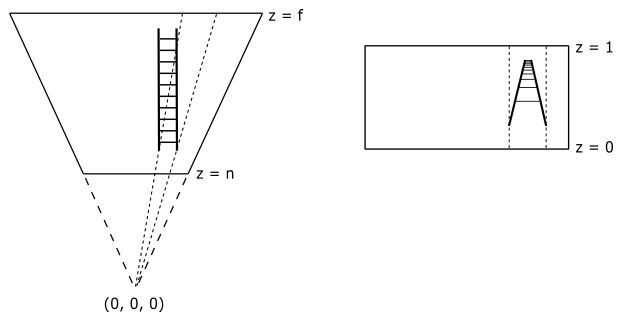

The illustration below depicts the frustum in view space (left) and the corresponding box in NDC space (right) after a perspective transformation. In DirectX, the NDC space is a left-handed system, with the y-axis that points upwards. The z-axis is always perpendicular to both the front and back faces of the box in NDC space and passes through their centers. While this arrangement also holds in view space, it is not an absolute requirement. Indeed, the z-axis in view space can be non-perpendicular to both the near and far planes, and it may pass through a point other than their centers.

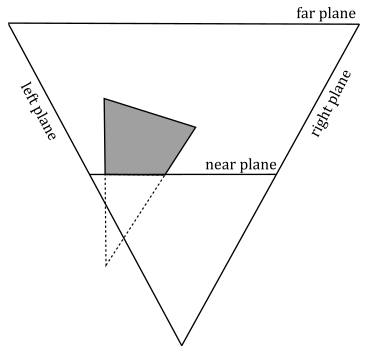

Now, you might be wondering what’s the point of this transformation. The following illustration shows a 2D representation from the top that explains what happens if you transform a frustum to a box. The objects inside the frustum are transformed accordingly, and the projection rays become parallel to each other. This way, we can orthographically project the mesh vertices onto a projection window (typically the front face of the box in NDC space) to mimic the perspective vision we are used to in real life, where objects like roads seem to converge in the distance, and where near objects appear bigger than distant ones.

Note

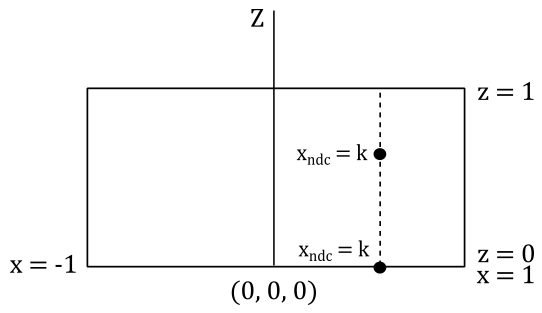

Interestingly, once we are in NDC space, there is no actual need for explicit projection onto the window plane. Indeed, as mentioned earlier, in NDC space the projection rays are parallel, and the z-axis is orthogonal to the front face of the NDC box, passing through its center (which is the origin of the NDC space). This means that the x- and y-coordinates of vertices remain constant along the projection rays in NDC space, only the z-coordinate varies. Consequently, the x- and y-coordinates of a vertex in NDC space are identical both inside the NDC box and when projected onto the front face (which lies in the \(z=0\) plane of the NDC space). The illustration below provides a top-down view that further demonstrates this concept. It shows that the x-coordinate of a vertex remains constant along the projection ray. The same applies to the y-coordinate if you look at the NDC space sideways.

Usually, that’s all we need to know in order to write applications that renders 3D objects on the screen using a perspective or orthographic effect. However, as graphics programmers, we are expected to know how things work under the hood. In particular, knowing how to build a projection matrix might come in useful in the future.

As stated in the note box above, once we go from view space to NDC space, we implicitly get a 2D representation of 3D vertex positions. So, this transformation is definitely related to the concept of projection. Indeed, the associated matrix is called projection matrix, that can vary depending on the type of projection we are interested in. We will start with a couple of matrices associated with the perspective projection, and then we will show the matrix associated with the orthographic projection.

Perspective projection#

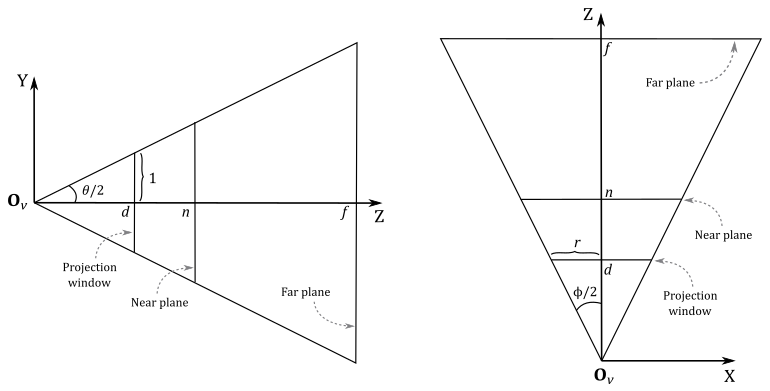

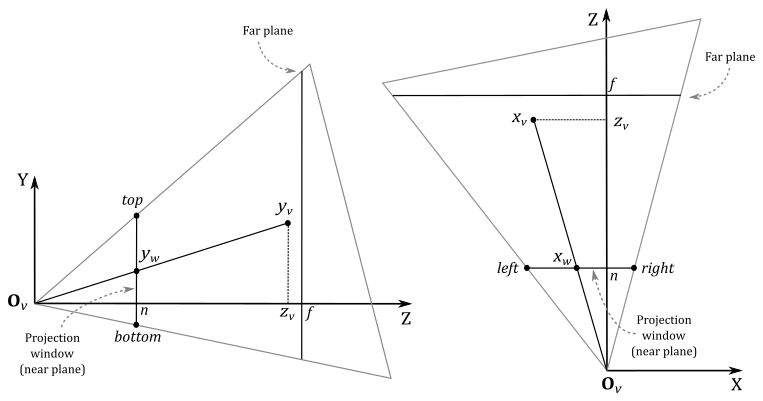

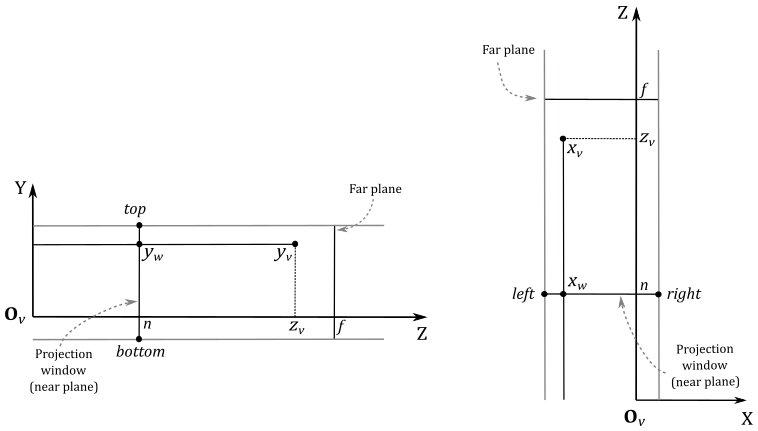

While DirectX offers convenient helper functions for constructing projection matrices, in this section we will explore the process of manually creating a couple of projection matrices based on frustum information. Our first objective is to derive NDC coordinates from view coordinates. Then, we will attempt to express the resulting equations in matrix form, with the goal of finding a projection matrix to go from the view space to the NDC space. Consider the following illustration.

Fig. 14 Frustum in view space#

To construct a projection matrix, we must first define a frustum (in view space) that provides the necessary information. Regarding the projection window, as explained in NDC space and Projection matrix, we can opt for the intersection between the pyramid formed by the camera and the near plane, with any plane parallel to the near one. For our purposes, let’s conveniently choose a plane at a distance \(d\) along the z-axis from the camera (located at the origin \(\mathbf{O}_v\) of the view space) so that the height of the projection window is \(2\).

The angle \(\theta\), known as the vertical FOV (field of view), allows us to control the vertical extent of the visible scene in view space. Notably, by setting \(\theta\) as the angle between the top and bottom sides of the frustum, we implicitly establish the distance \(d\), given our earlier requirement that the height of the projection window be \(2\). On the other hand, the angle \(\phi\) controls the horizontal FOV. This means we can zoom-in by simply decreasing \(\theta\) and\or \(\phi\), as this reduces the visible region, which results in fewer objects being projected onto the projection window. Conversely, if we increase \(\theta\) and\or \(\phi\) we have a zoom-out effect because more objects are projected onto the projection window.

However, the horizontal FOV \(\phi\) is not typically used directly to control the width of the projection window. Instead, we set the aspect ratio \(r\) of the window. This approach is crucial to prevent distortion when mapping the projection window onto the render target, which ultimately gets mapped to the window’s client area. Hence, we define \(r=w/h=w/2\), where \(w\) and \(h\) represent the width and length of the render target, respectively. Consequently, the width of the projection window is \(w=2r\). As depicted in the illustration above, the horizontal FOV \(\phi\) is dependent on both the aspect ratio \(r\) and the distance \(d\) of the projection window (which, in turn, depends on the vertical FOV \(\theta\)).

Observe that the z-axis is orthogonal to the projection window and passes through its center, dividing the height of the projection window into two parts of unit lengths. Also, the near and far planes are located at a distance of \(n\) and \(f\) units from the camera. This represents the most commonly used form of frustum, although it is just a specific case. We will explore a more general case later in this section.

Since the z-axis is orthogonal to the projection window and passes through its center, any 3D vertex projected onto its surface will have the y-coordinate already in NDC space (i.e., within the range \([-1, 1]\)). You can verify it in the illustration above, where the perspective projection \(y_w\) of the y-coordinate \(y_v\) of a 3D vertex in view space is always within the range \([-1, 1]\). On the other hand, the perspective projection \(x_w\) of the x-coordinate \(x_v\) of the same vertex in view space needs to be scaled by \(1/r\) to fit within the same range. As for the z-coordinate, it requires a separate discussion, which we will delve into shortly.

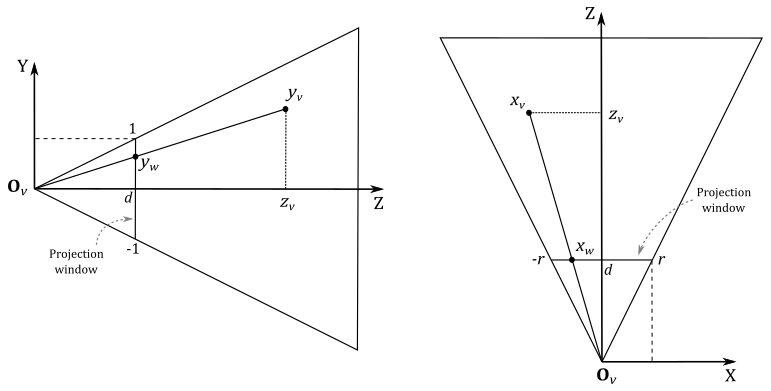

Let’s start by examining \(y_w\), which represents the perspective projection of the y-coordinate of a 3D vertex \(\mathbf{v}_v=(x_v, y_v, z_v, w_v)\) in view coordinates. The projection window lies in the plane \(z=d\). As mentioned at the begin of the section, we want to find a formula to derive NDC coordinates from view coordinates. To achieve this, let’s consider the triangles \(\triangle_1=(\mathbf{O}_v, d, y_w)\) and \(\triangle_2=(\mathbf{O}_v, z_v, y_v)\). These triangles are similar because they share an angle (the one at \(\mathbf{O}_v\)), and both have a right angle. So, we have

Also, we know that \(d\) depends on the vertical FOV \(\theta\). Indeed, you can check from image Fig. 14 that

If you want to compute the horizontal FOV \(\phi\), we have that

As for \(x_w\), we have a similar calculation. However, we need to consider the width of the projection window and the final scaling by \(1/r\) to derive the related NDC coordinate.

Observe that a vertex in view space \(\mathbf{v}_v=(x_v, y_v, z_v, w_v)\) is inside the frustum if and only if

where \(x_w\) and \(y_w\) are the first two coordinates of the projection of \(\mathbf{v}_v\) onto the projection window. As for the other two NDC coordinates, we have

As we know, a vertex position is a point, so the w-coordinate is always 1 regardless of the coordinate space. As for \(z_{ndc}\), there are additional considerations to take into account before deriving this NDC coordinate from the view one, so we will temporarily write a dummy \(z_{ndc}=z_{ndc}\).

However, before deriving \(z_{ndc}\) from \(z_v\), we can draw our first, unfortunate, conclusion: we cannot express in matrix form the transformation from view space to NDC space using equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) through \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces4}\). The reason is that a matrix form can be used if we have a linear combination of the rows of the matrix with the components of the vector as coefficients, as explained in Matrices and Transformations. The presence of the \(z_v\) term in the denominator of \(x_{ndc}\) and \(y_{ndc}\) (equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces2}\)) prevents us from directly representing the transformation as a matrix multiplication. Indeed, there’s no way to multiply a vector by a matrix and have a vector component appearing in the denominator of any coefficient within the linear combination of the matrix’s rows. So, we need to come up with something else to get a matrix form anyway.

Observe that if we multiply the NDC coordinates by \(z_v\) (equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) through \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces4}\)) we can derive a matrix form to transform a vertex from view space to a temporary space that is similar to NDC space, except for a division by \(z_v\). The trick is to place \(z_v\) in the w-component of the temporary coordinates and let the rasterizer perform the division by \(z_v\) for us. This operation is called perspective division because it is related to the perspective projection. Observe that we are using the last coordinate to hold a value that divides the other components, so this temporary space is an homogeneous space, as explained in Vectors. This homogeneous space is usually referred to as clip space (and its coordinates as clip coordinates) because it is a convenient space for discarding primitives outside the frustum and clipping primitives that intersect the frustum’s boundary (more on this shortly). Well, it turns out that clip coordinates are exactly what the rasterizer expects before performing perspective division, so we can use this trick to find a matrix form that transforms view coordinates into clip coordinates.

Note

The rasterizer expects to receive primitives with vertices in clip coordinates as input. Therefore, the last stage before the rasterizer must output vertices in clip space. Typically, if no optional stage is enabled, the last stage before the rasterizer is the vertex shader. Otherwise, it can be one between geometry shader and domain shader.

With the perspective division automatically performed by the rasterizer, we are able to transform the coordinates of a vertex from clip to NDC space. Now, we need to find a matrix form to go from view space to clip space. To do this, we must first multiply equations equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) through \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces4}\) by \(z_v\) to obtain the clip coordinates \(\mathbf{v}_c\), that represents the vertex in clip space.

Remember that we still need to derive \(z_{ndc}\) from the view coordinates of the vertex. Meanwhile, we can write the above equations in the following matrix form as follows:

Then, to get the NDC coordinates, we simply need to divide all the components of \(\mathbf{v}_c\) by \(z_v\) (operation automatically performed by the rasterizer; we will simply enjoy the result in the pixel shader).

We can now focus on deriving a formula for \(z_{ndc}\) starting from \(z_v\). Actually, we simply need to re-map \(z_v\) from \([n, f]\) (the range defined by the near and far planes of the frustum in view space) to \([0, 1]\) (the range defined by front and back faces of the corresponding box in NDC space). That is, we want the normalized distance between the vertex and the projection window (front face of the NDC box).

Note

As already mentioned several times in this section, we can intersect any plane with the pyramid between the camera and the near plane to obtain the projection window. The result represents the same projection window but at different distances from the camera. This difference in distance does not affect the x- and y-coordinates, as previously explained. However, it does impact the z-coordinate, which requires to be handled separately, as discussed in the current explanation.

Observe that \(n\) in view space is mapped to \(0\) in NDC space, while \(f\) is mapped to \(1\). Therefore, we need a scaling \(S\) to resize the range \([n, f]\) from \((f-n)\) to \(1\) (the size of the range \([0, 1]\)), plus a translation \(T\) to shift the scaled range so that it covers exactly the values in \([0, 1]\). Therefore, the generic equation is

Note

The equation above uses \(z_c\) (instead of \(z_{ndc}\)) to denote a clip coordinate. This is because the matrix in equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces5}\) transforms from view space to clip space, not directly to NDC space. However, this does not alter the observations made above: we still require a scaling operation followed by a translation to resize and remap the range of the z-coordinate, even in clip space. Indeed, the difference between clip and NDC coordinates can be seen a straightforward, additional scaling operation.

Consequently, the matrix in equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces5}\) becomes

because the last two entry in the third column are the only ones that can scale and translate the third coordinate of \(\mathbf{v}_v\), that is \(z_v\). To find \(S\) and \(T\), we can multiply the matrix above by a couple of vertices in view space which we already know the results in NDC space. For example, we know that for a vertex in view space that lies in the near plane we have \(z_{ndc}=0\) (since \(z_v=n\), and we know that \(n\) maps to \(0\)). So, if we multiply the vertex \(\mathbf{v}_v=(0, 0, n, 1)\) (which lies in the near plane) by the matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces6}\), we have

The coordinates of \(\mathbf{v}_c\) are in clip space, and after the perspective division (by \(w_c=n\)) we have

However, in this case we know that \(z_{ndc}=0\), so we have that

We also know that for a vertex in view space that lies in the far plane we have \(z_{ndc}=1\) (since \(z_v=f\), and we know that \(f\) maps to \(1\)). Therefore, if we multiply the vertex \(\mathbf{v}_v=(0,0,f,1)\) (which lies in the far plane) by the matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces6}\), we have

where we used \(T=-Sn\). After the perspective division (by \(w_c=f\)) we have

However, in this case we know that \(z_{ndc}=1\) so,

Substituting this into equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces7}\) we have

We just found the values of \(S\) and \(T\), so that we can write the z-coordinate both in clip space and in NDC space, after the perspective division, as follows:

Matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces6}\) now only depends on the distances of the near and far planes from the camera. This means that we can build this matrix by only using the frustum information at our disposal as follows:

Matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces10}\) can be used to transform vertex positions from view space to homogeneous clip space.

Although, that’s not what we wanted to find at the start of this section (the matrix to go from view to NDC space). However, since we get the perspective division for free during the rasterizer stage, we can actually consider \(\mathbf{P}\) as the perspective projection matrix to go from the view space to NDC space.

General case#

We built the perspective projection matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces10}\) with the assumption that the z-axis goes through the center of the projection window. However, in a more general case, we have a scenario similar to the one shown in the illustration below.

Deriving a perspective projection matrix for the general case won’t be overly difficult given our exploration of the specific case in the previuos section. Indeed, after projecting the 3D vertices onto the projection window, we need to translate the projection window so that the z-axis goes through its center again, bringing us back to the specific case. However, before proceeding, some initial observations are necessary.

In the general case, the frustum is not necessarily symmetrical with respect to the z-axis, so we can’t use the vertical FOV and aspect ratio to define the size of the projection window. Instead, we need to set its width and height by specifying the view coordinates of its top, bottom, left, and right sides.

We will project 3D vertices onto the projection window that lies on the near plane (meaning \(d=n\)). This isn’t really a limitation because we can project onto any projection window between the camera (exclusive) and near plane (inclusive).

Thus, in the general case, a vertex \(\mathbf{v}_v=(x_v, y_v, z_v)\) in view space is inside the frustum if and only if

where \(r, l, t\) and \(b\) are the view coordinates of the right, left, top and bottom sides of the projection window that lies on the near plane.

Therefore, we need to translate the first two coordinates of \(\mathbf{v}_w\) (projection of \(\mathbf{v}_v\)) so that the z-axis passes through the center of the projection window. As mentioned earlier, this brings the problem back to the specific case we have already examined.

Observe that we used the mid-point formula to subtract the x- and y- center coordinates of the projection window from \(x_w\) and \(y_w\), respectively. Now, to get the NDC coordinates, we need to scale their ranges. That is, since \(x_w\) is in the range \([l, r]\) and \(y_w\) is in the range \([b,t]\), we must re-map both to the range \([-1, 1]\). If we multiply \(x_w\) (as expressed in equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces11}\)) by \((t-b)^{-1}\) and \(y_w\) (as expressed in equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces12}\)) by \((r-l)^{-1}\), then both ranges will be in \([-0.5, 0.5]\). At that point, we only need to multiply by 2 to scale both ranges to \([-1, 1]\). These transformations are reflected in the following equations:

Now that we are back to the specific case, we can substitute equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) into equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces14}\), keeping in mind that we now have \(d=n\).

Similarly, we can substitute equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces2}\) (in particular, the second one of the three equations) into equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces13}\).

With equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces15}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces16}\), we have found a way to calculate the first two NDC coordinates from the corresponding view coordinates. As for \(z_{ndc}\), the equation remains unchanged from the one we derived in \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces8}\) for the specific case because the solution still involves to map the range \([n,f]\) to \([0,1]\).

If we omit the perspective division \((1/z_v)\) in \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces15}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces16}\), we can express the clip coordinates as a linear combination of the view coordinates. This means the perspective projection matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces10}\) becomes

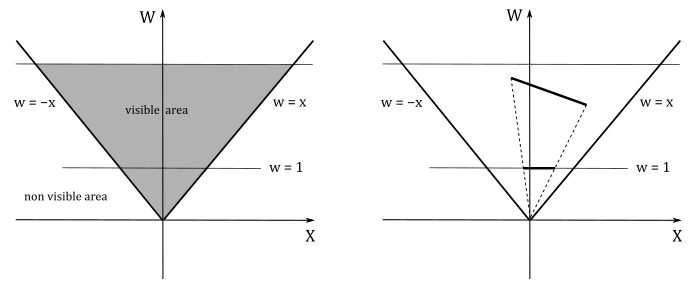

Perspective division and clipping#

After the perspective division by the w-component, the vertices inside the NDC box are the ones with NDC coordinates falling within the following ranges

This means that the vertices inside the frustum were the ones with homogeneous coordinates falling within the following ranges

That is, the vertices inside the frustum are the ones bounded by the following homogeneous planes (that is, 4D planes expressed in clip coordinates).

The following illustration shows a 2D representation of the frustum in the homogeneous xw-plane.

If \(w\ne 0\), we know that after the perspective division we always have \(w=1\). In this 2D case, the perspective division is essentially a projection onto the line \(w=1\). This means that a 2D object is projected to reduce its dimension to 1D. The same applies to objects in clip space: the perspective division projects object in a 4D space (the clip space) onto a 3D Cartesian space (the NDC space).

We have \(w=0\) if a vertex lies in the near plane. Indeed, in that case we have \(w=z_v=0\), which is the value the rasterizer uses to divide the other coordinates. To avoid divide-by-zero exceptions, as well as processing objects outside the visible region for nothing, the rasterizer clips primitives intersecting the planes of the frustum before executing the perspective division. Clipping is automatically performed by the rasterizer, so we won’t cover the implementation of an efficient clipping algorithm here. However, typically, a rasterizer simply clips primitives intersecting the near plane before the perspective division (in clip space), and discard non-visible pixels after the perspective division.

As you can see in the image above, a clipped primitive might no longer be a triangle. Therefore, the rasterizer also needs to triangulate clipped primitives, and re-inserts them in the pipeline.

Depth buffer precision#

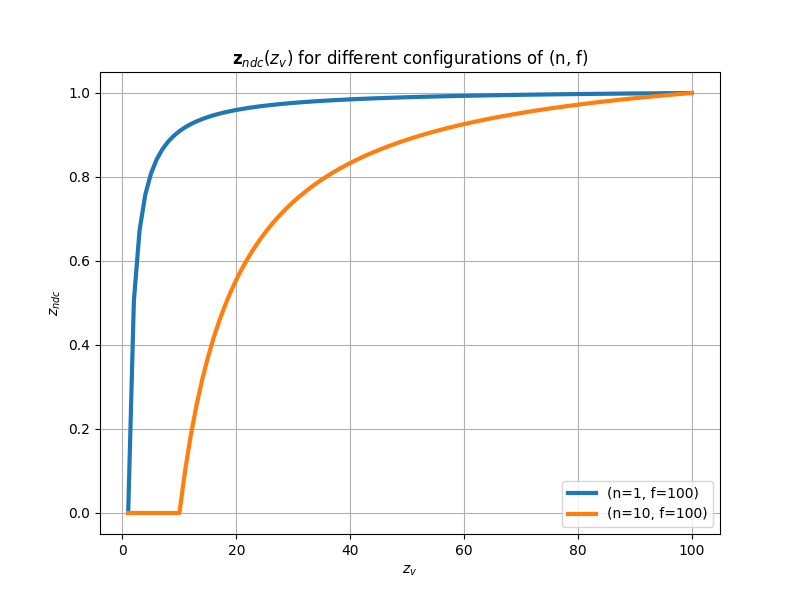

Whatever perspective projection matrix you decide to use (either \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces10}\) or \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces17}\)), after the perspective division we have

If you set \(n\) and \(f\), this equation represents a strictly increasing function of \(z_v\), with \(z_v=1\) acting as a horizontal asymptote. Mathematically, this implies that for every \(z_v\) value, there exists a unique corresponding \(z_{ndc}\). However, when working with computers, this property cannot be relied upon due to the finite precision of floating-point representations. Moreover, the density of representable floating-point values is higher near zero and decreases as values move further away.

The following graph shows what happens if you set \(n=1\) and \(f=100\). Approximately \(80%\) of the NDC values in the range \([0, 1]\) are available for less than \(5%\) of the view values in the range \([n,f]\). Consequently, the remaining \(95%\) of the view values must share the remaining \(20%\) of the NDC values. As a result, it is likely that different view values close to \(100\) cannot be represented by unique NDC values. In other words, different \(z_v\) values can produce the same \(z_{ndc}\) if the corresponding vertices are close to each other and far from the camera.

This can represent a serious problem because if a far object A is in front of another object B, but A is rendered after B, then A could be considered at the same distance as B with respect to the camera, and discarded from the pipeline if the depth test is enabled. We will delve into depth testing in a subsequent tutorial.

To mitigate the problem, we can set \(n\) and \(f\) to make the near and far planes as close as possible. In the illustration above, you can see what happens if we set \(n=10\) and \(f=100\). The function grows slower, so we have a more even distribution of NDC values. Another mitigation technique is to redesign the projection matrix so that the clip space depths \(z_c\) are still mapped to \([0,1]\), but in reverse order. That is, after the perspective division we have that \(z_{ndc}\) is a strictly decreasing function, where the NDC values are much more evenly distributed between near and far planes. Additional details on the inverse projection matrix will be provided in a subsequent tutorial.

Orthographic projection#

Similar to the general case of perspective projection, in orthographic projections, we aim to align the z-axis with the center of the projection window. However, unlike perspective projections, the location of the projection window along the z-axis is irrelevant in orthographic projections. This unique property will allow us to simplify the derivation of an equation for \(z_{ndc}\).

Indeed, we can reuse equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces11}\) through \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces14}\) to align the z-axis through the center of the projection window and derive the first two NDC coordinates. However, this time, we can’t reuse any equations formulated for the z-coordinate in the previous sections because they were derived in the context of a perspective projection (i.e., we found the variables \(S\) and \(T\) inside a perspective projection matrix; see \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces6}\)).

With an orthographic projection, we can derive an equation for \(z_{ndc}\) by considering that we can move the projection window along the z-axis of the view space without any consequences. So, to map \([n,f]\) to \([0,1]\), we can translate the coordinate \(z_w\) (similar to how we did with \(x_w\) and \(y_w\)) to make the x- and y-axes of the view space pass through the center of the box between the near and far planes. Then, we can scale the result by \((f-n)^{-1}\) (to normalize the range) and eventually translate it by \(1/2\) to shift from \([-0.5, 0.5]\) to \([0, 1]\).

Observe that, with an orthographic projection, we can’t substitute \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces2}\) into \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces14}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces13}\) because, as illustrated in the image above, now we have \(x_w=x_v\) and \(y_w=y_v\), along with \(z_w=z_v\) since we aim to preserve the depth value (i.e., we don’t project it onto the projection window). These are the values we need to plug into \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces14}\), \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces13}\), and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces18}\).

The result is that we no longer have the \(z_v\) term in the denominators of the NDC coordinates. This means that the NDC coordinates can be expressed as a linear combination of the view coordinates, so that we can build our orthographic projection matrix directly from equations \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces19}\), \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces20}\) and \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces21}\), defining the NDC coordinates.

In conclusion, the matrix above allows us to go straight from view space to NDC space, without passing through the homogeneous clip space. Although, the rasterizer still expects vertices in clip coordinates. Therefore, we need a way to make the rasterizer believe we are passing clip coordinates, while also avoiding the perspective division. As you can see in the fourth column of the orthographic projection matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces22}\), the unitary value has moved in the last element. This means that if you multiply a vertex by this matrix you will get 1 in the last component of the resultant vector. That way, the rasterizer will divide the remaining components by 1, which nullifies the effect of the perspective division.

Projection matrices in DirectX#

DirectXMath provides many useful functions for building different types of projection matrices, depending on the type of projection and the handedness of the frame. However, in this tutorial series we will only work with left-handed coordinate systems. Therefore, to build a perspective projection matrix we can use the helper function XMMatrixPerspectiveFovLH.

XMMATRIX XMMatrixPerspectiveFovLH(

float FovAngleY,

float AspectRatio,

float NearZ,

float FarZ

);

As you can see, we only need to pass the vertical FOV, the aspect ratio, and the distances of the near and far planes. This means that with this function we can build the matrix \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces10}\), related to the particular case of a perspective projection, as discussed in section Perspective projection ─ remember that \(d\) can be derived from the vertical FOV (see equation \(\eqref{eq:ASpaces1b}\)).

As for the general case of a perspective projection, we can use the helper function XMMatrixPerspectiveOffCenterLH.

XMMATRIX XMMatrixPerspectiveOffCenterLH(

float ViewLeft,

float ViewRight,

float ViewBottom,

float ViewTop,

float NearZ,

float FarZ

);

To build an orthographic projection matrix, we can use the helper function XMMatrixOrthographicOffCenterLH.

XMMATRIX XMMatrixOrthographicOffCenterLH(

float ViewLeft,

float ViewRight,

float ViewBottom,

float ViewTop,

float NearZ,

float FarZ

);

Refer to the DirectXMath library’s source code to verify that these projection matrices are implemented according to the definitions presented in this tutorial.

DirectXMath also provides XMMatrixPerspectiveLH. Please refer to the official API documentation for more details.

Render target space and Viewport#

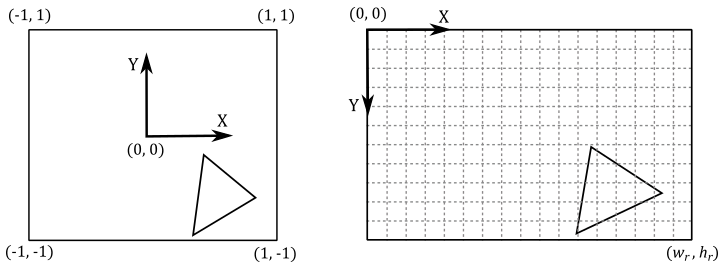

After the perspective division, all vertices are in NDC space, and if we only consider the first two NDC coordinates, we also have their 2D representations. Although, we are in a normalized 2D space (the \([-1,1]\times [-1,1]\) front face of the NDC box) and we need to map it onto the render target in order for the rasterizer to determine the pixels covered by the primitives at specific render target positions, typically the centers of the texels.

The rasterizer automatically transforms the vertices from NDC space to render target space by using the viewport information we set with ID3D12GraphicsCommandList::RSSetViewports. Once in render target space, it can generate pixels covered by primitives. However, if the render target coordinates of a pixel fall outside the specified render target size, the pixel will be discarded and won’t be processed by any subsequent stage of the pipeline.

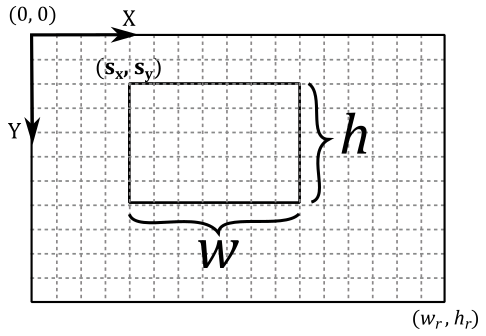

In Hello Window, we briefly mentioned that a viewport can be seen as a rectangular region within the back buffer space where rendering operations take place. Now, we can be more specific in stating that a viewport is a structure that holds the necessary information for the rasterizer to construct a matrix that transforms vertices from NDC space to a specific rectangle within the render target space. In other words, it defines the mapping of the projection window onto a selected area of the render target.

Since we might find it useful in the future, let’s see how we can manually build this matrix to go from NDC space to render target space from the viewport information. Suppose we want to draw on a selected \(w\times h\) rectangle within the render target (that is, we want to map the front face of the NDC box onto a rectangular area of the back buffer). This means that we want to map the following NDC ranges

to the following render target ranges

Starting with the x-coordinate, we need to map \([-1, 1]\) to \([0,w]\). For this purpose, we can divide \([-1, 1]\) by \(2\) to normalize the range, which becomes \([-0.5, 0.5]\). Then, we can multiply by \(w\) to get \([-w/2, w/2]\). Lastly, we add \(w/2\) to get \([0, w]\).

As for the y-coordinate, we need to consider the change of direction between NDC and render target space. That is, \(y=1\) in NDC space is \(y=0\) in render target space, while \(y=-1\) in NDC space is \(y=h\) in render target space. Therefore, we need to map \([-1, 1]\) to \([h, 0]\). Like we did for the x-coordinate, we start dividing \([-1, 1]\) by \(2\) to normalize the range, which becomes \([-0.5, 0.5]\). Then, we multiply by \(h\) to get \([-h/2, h/2]\), and then by \(-1\) to reverse the range, which becomes \([h/2,-h/2]\). Lastly, we add \(h/2\) to get \([h, 0]\).

As for the z-coordinate, we only need to scale \([0, 1]\) by \((z_{max}-z_{min})\) to get \([0,\ (z_{max}-z_{min})]\), and then add \(z_{min}\) to get \([z_{min},\ z_{max}]\).

At this point, we only need to translate the resulting coordinates to shift the origin of the \(w\times h\) rectangle to the position \((s_x,s_y)\) in render target space. So, the range \([0, w]\) becomes \([s_x,\ w+s_x]\), while the range \([0,h]\) becomes \([s_y,\ h+s_y]\). That way, we can map the 2D (normalized) projection window to the render target, starting from the position \((s_x,s_y)\) for \(w\) units along the x-axis, and \(h\) units along the y-axis.

Now, we can derive our render target coordinates \((x_r, y_r, z_r)\) with respect to the NDC ones as follows.

Note

If the resulting render target coordinates fall outside the render target size, then the corresponding pixel generated by the rasterizer will be discarded. That is, it won’t be processed by subsequent stages of the pipeline.

In matrix form this becomes

Although, most of the time, we don’t want to rescale the NDC z-coordinate, so we have \(z_{min}=0\) and \(z_{max}=1\), and thus \(z_r=z_{ndc}\)

Tip

To prevent stretching in the final image on the screen, it’s recommended to set \(w\) and \(h\) so that aspect ratio of the projection window matches the aspect ratio of the render target, and the window’s client area as well.

Once mesh vertices are in render target space, the rasterizer can identify the texels covered by the primitives, and emit pixels at the corresponding positions to be consumed by the pixel shader.

Support this project

If you found the content of this tutorial somewhat useful or interesting, please consider supporting this project by clicking on the Sponsor button below. Whether a small tip, a one-time donation, or a recurring payment, all contributions are welcome! Thank you!

References#

S. Marschner and P. Shirley. Fundamentals of Computer Graphics. CRC Press, 4th edition, 2022.