Hello Frame Buffering#

Introduction#

In previous tutorials, we used CPU and GPU in a sequential, suboptimal way. Indeed, we used a single command allocator to record drawing commands for two buffers in the swap chain. This means that, to avoid overwriting commands still in use by the GPU, we had to flush the command queue before recording new commands for creating the next frame – since all commands were recorded in the same memory location. This resulted in a sequential workflow: the CPU recorded the commands to create a frame and waited for the GPU to complete the actual rendering work. In other words, we were not able to create frames in advance on the CPU timeline with respect to the GPU. This tutorial addresses the problem by introducing a separate command allocator for each buffer in the swap chain.

The sample we will review in this tutorial (D3D12HelloFrameBuffering) is not much different from the samples we examined so far, as it simply shows a triangle on the screen (I changed the background color of the screenshot above to visually distinguish it from the screenshots of previous tutorials). However, for the first time, we will take advantage of the parallelism between CPU and GPU by creating frames in advance on the CPU timeline.

CPU-GPU parallelism#

Before discussing how to unleash parallelism between CPU and GPU, it can be useful to revisit the explanation provided in a previous tutorial regarding frame presentation, which is replicated below for convenience.

from Hello Window

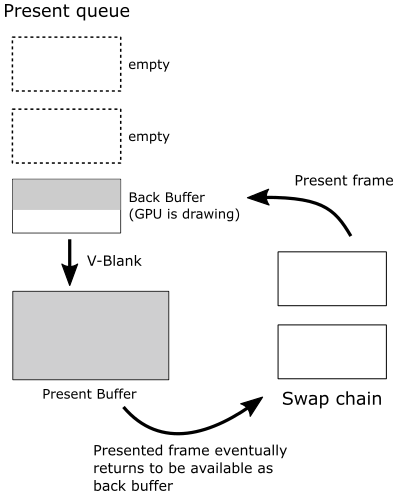

IDXGISwapChain::Present allows presenting (to the user, on the screen) the frame just created on the CPU timeline (using the current back buffer as the render target). How does it work? Present operations occur on the graphics queue associated with the swap chain. That is, when you call Present, a present operation is recorded in the command queue associated with swap chain during its creation, and a request to present the frame is inserted in a queue called the present queue, waiting for the GPU to execute the commands to draw on the related back buffer. Since this happens only after recording all the commands needed to create the frame, you are sure the GPU reached the present operation in the command queue only at the very end (i.e., after executing all the other previous drawing commands). At that point, the frame associated with the request in the present queue is done, ready to be shown on the screen at the next vertical interval when the swap/flip between the back and present buffers takes place.

Important

When you create a frame and present it on the CPU timeline, nothing happens on the related back buffer until the GPU starts executing drawing commands in the related command list.

Note

Present also updates the index of the current back buffer in the swap chain so that the next frame will be created on the other buffer when it becomes available again as a render target.

Observe that Present takes, as its first parameter (called SyncInterval), a value that specifies how to synchronize the presentation of a frame with the vertical blank. For values greater than zero, it indicates the number of vertical intervals the frame waits in the present queue before getting ready to be presented on the screen, enabling v-sync. In this sample, we always pass 1 as an argument to this parameter to specify that we want to wait a single vertical interval. In a later tutorial, we will explore what it means if you pass 0 to this parameter.

While this explanation provides a basic understanding on frame presentation, it offers an oversimplified view of how frames are actually presented on the screen. Indeed, when a frame is presented, various factors can affect the presentation process, which depends on the presentation model (specified in the swap chain), window mode (full screen or windowed), and V-Sync settings (on or off). However, exploring every possible combination is beyond the scope of this tutorial. Therefore, I will focus on explaining what happens in the D3D12HelloFrameBuffering sample (and previous ones as well), where we create a swap chain that uses the flip model to present frames on the screen, with a window that cannot be switched to full screen, and V-Sync enabled (that is, when we pass 1 to SyncInterval). Other combinations will be covered in later tutorials.

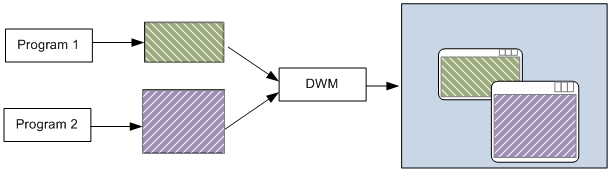

By specifying the flag DXGI_SWAP_EFFECT_FLIP_DISCARD during swap chain creation, we indicate our intention to use the flip model to present frames on the screen. When this model is employed with windowed applications (i.e., not full screen), a system service called the Desktop Window Manager (DWM) wakes up at every vertical blank and retrieves the latest completed back buffer in the swap chain of all graphics applications running on the desktop (including the offscreen buffers of all “normal” windowed applications). It then composes the final image of the entire desktop into its own back buffer, which will be displayed on the screen at the next vertical interval, when it becomes the present buffer.

Let’s use a practical example to explain in more detail what happens in the D3D12HelloFrameBuffering sample under the conditions outlined above, where the flip model is used with a swap chain that includes two buffers for rendering in an application running in windowed mode. This will also allow us to illustrate how to unlock parallelism between CPU and GPU. For convenience, we’ll refer to the two buffers in the swap chain as A and B.

As soon as we start the application, the commands to draw the very first frame on buffer A are recorded in a command list. Then, ExecuteCommandLists and Present are invoked to send the command list to the command queue and insert the first frame into the present queue, respectively. As a consequence, a present operation is also added to the command queue after the command list.

Note

Until now, we have only created the frame on the CPU timeline. By recording drawing commands in a command list and calling Present, we have simply submitted instructions to the GPU. The actual rendering process on the associated back buffer will not begin until the GPU starts executing those commands from the command queue.

Provided that we don’t overwrite the memory space managed by the command allocator for the command list operating on buffer A (e.g., using a new allocator for the command list operating on buffer B), we can start creating (on the CPU timeline) the second frame with buffer B as the render target. We can queue this new frame with the confidence that the GPU won’t write onto buffer B before it finishes drawing on buffer A, or if buffer B is unavailable.

Note

When command lists are submitted to the same command queue through separate calls to ExecuteCommandLists, strict sequential execution is guaranteed. This means that the GPU processes them in the same order they were submitted, ensuring each command list completes before the next one begins.

However, submitting multiple command lists together within a single ExecuteCommandLists call provides weaker ordering guarantees. The GPU typically start execution in submission order, but it may not necessarily finish them in the same order. It is free to start processing new command lists (in parallel) even before older ones have completed.

Note

A buffer is said to be available if there are no outstanding present operations that reference it, and it is currently not being displayed by the system. Otherwise, it is unavailable.

A frame is considered ready to be shown on the screen when the GPU met the related present operation in the command queue, and if the synchronization time associated with the presentation of the frame in the present queue expired.

A frame is retired from the present queue if discarded by the DWM (more on this shortly), or when replaced by a new frame as the one displayed on the screen.

At this point, we need a mechanism to know when buffers A and B can be reused as render targets to create new frames. Fences effectively serve this purpose. By appending a fence after each command list submitted to the command queue, we can synchronize CPU and GPU operations. Concretely, the CPU waits for the GPU to signal a fence before creating a new frame. This guarantees that no pending commands remain in at least one of the submitted command lists (or rather, in the corresponding memory space managed by the command allocator). Consequently, we can confidently create and present new frames as long as the present queue has sufficient space to accommodate new frames (default is three slots, adjustable as needed) and provided that the back buffer we want to use as the render target is available. Otherwise, a Present call will block until a frame is retired from the present queue, which makes the back buffer available again for reuse and creates space in the present queue for a new frame.

Important

While creating as many frames as possible in advance on the CPU timeline may seem like a good idea, this approach has a downside. Specifically, creating too many frames in advance can increase present or frame latency, the time it takes for a frame to be displayed on the screen after it has been created on the CPU timeline. This means that there is a trade-off between reducing idle time (for both the CPU and GPU) by creating frames in advance and minimizing frame latency to ensure a responsive and smooth user experience. It is important to carefully balance these two factors to achieve optimal performance and efficiency in our applications.

Note

Because we usually send command lists to the command queue (with ExecuteCommandLists) before calling Present, the rendering work of the GPU could be paused\queued, and resume once the back buffer is available (when the frame that used the back buffer as render target is retired from the present queue).

Regardless of how many frames are presented (on the CPU timeline) and completed (on the GPU timeline), at the next vertical interval the DWM wakes up and gets the latest completed frame to start composing the entire desktop. In the D3D12HelloFrameBuffering sample, composition involves copying the latest completed swap chain back buffer to the DWM’s back buffer, which is then sent to the display hardware at the next vertical interval as the actual present buffer. After this copy operation, the frame is considered queued and then finally displayed when the hardware is ready to do it. Once a new frame is queued, the displayed one, along with others that missed the chance to be presented on the screen due to a newer completed frame being available for the DWM, can be retired from the present queue. Note that, in this scenario, the actual flip happens between the back and present buffers of the DWM.

Note

As mentioned earlier, when command lists are submitted through separate calls to ExecuteCommandLists, they are processed and completed in order. In this scenario, if a frame in the present queue is retired because a newer completed frame is available for the DWM, we can be confident that that the corresponding command list has already been executed. Consequently, we are free to overwrite the memory space holding the related commands, and the GPU can reuse the associated back buffer for subsequent drawing operations.

Command lists are the only resource requiring explicit synchronization (using fences) during presentation. On the other hand, swap chain buffers are automatically synchronized by the API and the driver for presentation purposes. Nevertheless, we still need to synchronize render targets with resource transitions for rendering purposes.

Important

The note above refers to resource synchronization during presentation and rendering. However, during frame creation on the CPU timeline, we still need to preserve\synchronize all the GPU resources (buffers, descriptors, synchronization objects, etc.) that our application accesses with write operations to create a frame. For this purpose, we can, for example, provide multiple copies of those resources (one for each frame we want to create in advance on the CPU timeline). This way, frame creation won’t interfere with other pending frames in GPU queues because resources that will be used on the GPU timeline to render pending frames are preserved during the creation of new frames on the CPU timeline that access the same resources.

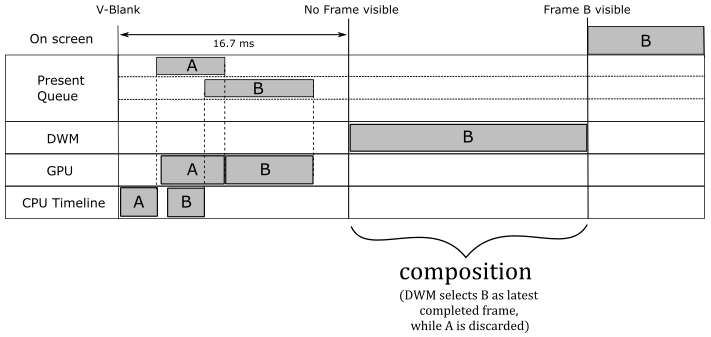

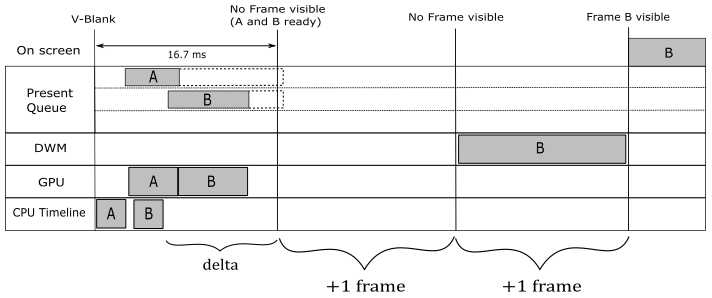

Coming back to our example, we can start creating a new frame on the CPU timeline (the third, with buffer A as the render target) once the fence gets signaled the first time. Indeed, at that point, we can be sure that the GPU has finished executing the command list for the first frame, which also used buffer A. Observe that, if the first frame in the present queue hasn’t been displayed yet, the subsequent call to Present (used to present the third frame) will block until the first frame is retired from the present queue. In this scenario, it is possible to have two frames in the present queue (both the first using buffer A and the second using buffer B). If the GPU is fast enough to complete both of them before the next vertical blank, the DWM will select the second frame (the last completed one) while the first one is immediately retired from the present queue. Since the GPU has undoubtedly executed the command lists of both the first two frames, we would eventually be able to create the third frame on the CPU timeline with A as the render target and present it. Indeed, once the first frame becomes retired, the Present waiting on the CPU timeline can unblock to queue the third frame, and the GPU can execute the corresponding command list. After this third frame becomes queued, the second one can be retired from the present queue. And so on.

Unfortunately, the assistance provided by the DWM in the presentation process comes at a cost. It introduces a presentation latency of a bit more than a vertical interval, at least (but it can be more). The DWM takes one vertical interval to compose the desktop image, and this needs to be added to the time the GPU requires to complete the frame. However, things can worsen when v-sync is on, as illustrated in the image below. In that case, you need to add at least another vertical interval to the presentation latency because each frame has to wait for the synchronization time associated with its presentation before becoming ready. This means that the composition using a frame just completed will be the one executed by the DWM woken up at the next v-sync ─ that is, the frame misses a composition.

Note

As mentioned at the beginning of the tutorial, the Present function takes, as its first parameter, a value that specifies how to synchronize the presentation of a frame with the vertical blank. We already know what happens by passing 1 or greater values. On the other hand, by passing 0 the remaining time on the previously presented frame in the present queue will be cancelled, while the frame you are presenting will be discarded if a newer one becomes queued.

In conclusion, we can state that by using a different command allocator for each buffer in the swap chain and employing a fence after each command list in the command queue for synchronization purposes, we can create frames in advance on the CPU timeline, unleashing parallelism between the CPU and GPU. However, remember that creating frames too far in advance can result in noticeable present latency. Furthermore, preserving the state of all GPU resources modified during frame creation on the CPU timeline is also essential for correct rendering.

D3D12HelloFrameBuffering: code review#

Now, we are ready to review the code of the sample. Let’s start with the application class.

class D3D12HelloFrameBuffering : public DXSample

{

public:

D3D12HelloFrameBuffering(UINT width, UINT height, std::wstring name);

virtual void OnInit();

virtual void OnUpdate();

virtual void OnRender();

virtual void OnDestroy();

private:

// In this sample we overload the meaning of FrameCount to mean both the maximum

// number of frames that will be queued to the GPU at a time, as well as the number

// of back buffers in the DXGI swap chain. For the majority of applications, this

// is convenient and works well. However, there will be certain cases where an

// application may want to queue up more frames than there are back buffers

// available.

// It should be noted that excessive buffering of frames dependent on user input

// may result in noticeable latency in your app.

static const UINT FrameCount = 2;

struct Vertex

{

XMFLOAT3 position;

XMFLOAT4 color;

};

// Pipeline objects.

CD3DX12_VIEWPORT m_viewport;

CD3DX12_RECT m_scissorRect;

ComPtr<IDXGISwapChain3> m_swapChain;

ComPtr<ID3D12Device> m_device;

ComPtr<ID3D12Resource> m_renderTargets[FrameCount];

ComPtr<ID3D12CommandAllocator> m_commandAllocators[FrameCount];

ComPtr<ID3D12CommandQueue> m_commandQueue;

ComPtr<ID3D12RootSignature> m_rootSignature;

ComPtr<ID3D12DescriptorHeap> m_rtvHeap;

ComPtr<ID3D12PipelineState> m_pipelineState;

ComPtr<ID3D12GraphicsCommandList> m_commandList;

UINT m_rtvDescriptorSize;

// App resources.

ComPtr<ID3D12Resource> m_vertexBuffer;

D3D12_VERTEX_BUFFER_VIEW m_vertexBufferView;

// Synchronization objects.

UINT m_frameIndex;

HANDLE m_fenceEvent;

ComPtr<ID3D12Fence> m_fence;

UINT64 m_fenceValues[FrameCount];

void LoadPipeline();

void LoadAssets();

void PopulateCommandList();

void MoveToNextFrame();

void WaitForGpu();

};

At this point, the comment on the FrameCount variable should be clear: if you keep creating frames in advance on the CPU timeline, at some point either the CPU (after the call to Present) or the GPU (during the rendering work) will end up waiting for a back buffer to become available again, increasing the present latency.

In this sample, we need two command allocators because we are going to queue two frames to the GPU before waiting on the CPU timeline. As you know, we can reuse the same command list object, provided that we don’t overwrite the memory holding the corresponding commands if they have not yet been executed by the GPU.

As explained earlier, we need to preserve GPU resources accessed with write operations during frame creation on the CPU timeline. This is why we also need two different fence values to delimit (in the command queue) the command lists of the two frames we want to queue. This way, we can be notified when the GPU finishes drawing one of them, so that we can resume creating frames on the CPU timeline.

We will use WaitForGPU to flush the command queue. On the other hand, MoveToNextFrame only waits until the GPU finishes drawing at least one (the oldest) of the two queued frames. In other words, it checks if we can continue creating frames on the CPU timeline.

The LoadPipeline function now creates two command allocators, so the call to the CreateCommandAllocator function has been placed inside a for loop.

// Load the rendering pipeline dependencies.

void D3D12HelloFrameBuffering::LoadPipeline()

{

// ...

// Create frame resources.

{

CD3DX12_CPU_DESCRIPTOR_HANDLE rtvHandle(m_rtvHeap->GetCPUDescriptorHandleForHeapStart());

// Create a RTV and a command allocator for each frame.

for (UINT n = 0; n < FrameCount; n++)

{

ThrowIfFailed(m_swapChain->GetBuffer(n, IID_PPV_ARGS(&m_renderTargets[n])));

m_device->CreateRenderTargetView(m_renderTargets[n].Get(), nullptr, rtvHandle);

rtvHandle.Offset(1, m_rtvDescriptorSize);

ThrowIfFailed(m_device->CreateCommandAllocator(D3D12_COMMAND_LIST_TYPE_DIRECT, IID_PPV_ARGS(&m_commandAllocators[n])));

}

}

}

Now, let’s see what’s new in LoadAssets.

// Load the sample assets.

void D3D12HelloFrameBuffering::LoadAssets()

{

// ...

// Create synchronization objects and wait until assets have been uploaded to the GPU.

{

ThrowIfFailed(m_device->CreateFence(m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex], D3D12_FENCE_FLAG_NONE, IID_PPV_ARGS(&m_fence)));

m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex]++;

// Create an event handle to use for frame synchronization.

m_fenceEvent = CreateEvent(nullptr, FALSE, FALSE, nullptr);

if (m_fenceEvent == nullptr)

{

ThrowIfFailed(HRESULT_FROM_WIN32(GetLastError()));

}

// Wait for the command list to execute; we are reusing the same command

// list in our main loop but for now, we just want to wait for setup to

// complete before continuing.

WaitForGpu();

}

}

First, we create a fence with a value of 0 ─ m_fenceValues is initalized to {0, 0} in the constructor of the D3D12HelloFrameBuffering class (refer to the complete source code of the sample). Next, we increment the value of the fence used to delimit the command list for the initialization phase. This will allow us to distinguish between different command lists in the command queue. Finally, we create an event and call the WaitForGpu function to flush the command queue after the initialization phase.

// Wait for pending GPU work to complete.

void D3D12HelloFrameBuffering::WaitForGpu()

{

// Schedule a Signal command in the queue.

ThrowIfFailed(m_commandQueue->Signal(m_fence.Get(), m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex]));

// Wait until the fence has been processed.

ThrowIfFailed(m_fence->SetEventOnCompletion(m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex], m_fenceEvent));

WaitForSingleObjectEx(m_fenceEvent, INFINITE, FALSE);

// Increment the fence value for the current frame.

m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex]++;

}

The implementation of the WaitForGPU function is similar to that of the old WaitForPreviousFrame function used in previous samples, as its purpose is to flush the command queue. First, we insert into the command queue a fence with a value associated with the command list of the “current frame” (or rather, rendering work, as we will use this function to flush the command queue after the initialization phase). Then, we wait for the GPU to meet and signal this fence. At that point, we are sure there are no commands left to execute in the command queue. Finally, we increment the fence value to delimit the command list of the next frame.

Observe that we “wasted” the fence value 1 to flush the command queue after the initialization phase. Therefore, we need a new fence value to delimit the first frame. Currently, the first element of the array m_fenceValues has a value of 2, which will be used to delimit the command list of the first frame, while the second element of m_fenceValues is still 0, and will be used to track the command list of the second frame.

In OnRender, we now use the MoveToNextFrame function instead of the older WaitForPreviousFrame to synchronize the presentation of the frames created in advance on the CPU timeline.

// Render the scene.

void D3D12HelloFrameBuffering::OnRender()

{

// Record all the commands we need to render the scene into the command list.

PopulateCommandList();

// Execute the command list.

ID3D12CommandList* ppCommandLists[] = { m_commandList.Get() };

m_commandQueue->ExecuteCommandLists(_countof(ppCommandLists), ppCommandLists);

// Present the frame.

ThrowIfFailed(m_swapChain->Present(1, 0));

MoveToNextFrame();

}

// Prepare to render the next frame.

void D3D12HelloFrameBuffering::MoveToNextFrame()

{

// Schedule a Signal command in the queue.

const UINT64 currentFenceValue = m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex];

ThrowIfFailed(m_commandQueue->Signal(m_fence.Get(), currentFenceValue));

// Update the frame index.

m_frameIndex = m_swapChain->GetCurrentBackBufferIndex();

// If the next frame is not ready to be rendered yet, wait until it is ready.

if (m_fence->GetCompletedValue() < m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex])

{

ThrowIfFailed(m_fence->SetEventOnCompletion(m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex], m_fenceEvent));

WaitForSingleObjectEx(m_fenceEvent, INFINITE, FALSE);

}

// Set the fence value for the next frame.

m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex] = currentFenceValue + 1;

}

In MoveToNextFrame, we first initialize the currentFenceValue local variable with the fence value that will delimit the command list of the current frame. Subsequently, we place a fence with that value in the command queue since the command list of the current frame has already been submitted in OnRender.

GetCurrentBackBufferIndex returns the index of the back buffer where we will draw the next frame (updated in OnRender by the call to Present). However, since we are still processing the current frame, we can use this index to get the fence value of the previous frame as well. At this point, using m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex], we obtain the fence value of the frame before the current one, given that we only alternate between two frames/buffers: the current and the previous ones (the next frame will overwrite the previous one, but at that point, we consider it the current frame).

The if block is not entered if the value of the last fence the GPU encountered in the command queue is greater than or equal to the fence value of the previous frame. Indeed, only in that case can we be sure that the GPU has finished drawing the previous frame, allowing us to reuse the related command list and allocator to create the next frame.

Finally, we set the fence value of the next frame to the incremented fence value of the current frame, ensuring a clear distinction between the two frames we can queue to the GPU.

Whenever MoveToNextFrame returns, we are ready to create another frame on the CPU timeline.

Above I just explained the theory behind MoveToNextFrame. Now, it can be useful to see what happens in practice.

On the first call to MoveToNextFrame, currentFenceValue is 2 (to delimit the first frame), while m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex] is 0 after the call to GetCurrentBackBufferIndex since this is still the fence value of the “previous” frame ─ obviously, there are no frames before the first one, but we haven’t drawn the second frame yet, so we can use its fence value to reference a dummy previous frame. GetCompletedValue returns at least 1, as it was the value of the fence the GPU had already encountered when we flushed the command queue by calling WaitForGPU in LoadAssets. Therefore, we won’t enter the if block. At the end, we set the fence value of the next frame to the incremented fence value of the current frame (i.e., we set 3 to m_fenceValues[m_frameIndex] because the fence value of the current frame is 2).

On the next call to MoveToNextFrame, currentFenceValue will be 3, while the fence value of the previous frame will be 2. So, we won’t enter the if block unless GetCompletedValue returns a value less than 2, indicating that the GPU has not finished drawing the previous frame yet. And so on.

Source Code#

D3D12HelloWorld (DirectX-Graphics-Samples)

Support this project

If you found the content of this tutorial somewhat useful or interesting, please consider supporting this project by clicking on the Sponsor button below. Whether a small tip, a one-time donation, or a recurring payment, all contributions are welcome! Thank you!